Devilish devices or farmyard friends?

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 1 (Spring 2004), Volume 12 Ewan Morris recounts the heated debate provoked by the introduction of Percy Metcalfe’s coinage designs in 1928.

Ewan Morris recounts the heated debate provoked by the introduction of Percy Metcalfe’s coinage designs in 1928.

The introduction of the euro has finally seen the disappearance of Percy Metcalfe’s animal designs from the coinage of the Republic of Ireland, almost 75 years after they first appeared on the Free State’s coins. Although decimalisation had already led to a reshuffle of Metcalfe’s designs, with some being taken out of circulation and replaced by new designs, the rest continued to be a familiar part of everyday life in the Republic. Indeed, so familiar and commonplace did they become that it is hard now to believe that their release in 1928 was followed by a heated debate about their symbolism.

Design committee chaired by W.B. Yeats

Minister for Finance Ernest Blythe-‘a coinage distinctively our own, bearing the devices of this country’. (George Morrison)

In January 1926, Minister for Finance Ernest Blythe introduced the Coinage Bill into Dáil Éireann. He told the Dáil that it was natural that the Free State should have ‘a coinage distinctively our own, bearing the devices of this country’. In the Senate, poet W.B. Yeats welcomed the government’s decision to appoint a committee of artists to advise on the design of the coins, declaring that stamps and coins were ‘the silent ambassadors of national taste’. Yeats was therefore a logical choice as chairman of the committee on coinage design, a position to which he was appointed in May 1926. He was joined on the committee by Thomas Bodkin, a governor of the National Gallery of Ireland; Dermod O’Brien, president of the Royal Hibernian Academy; Lucius O’Callaghan, director of the National Gallery of Ireland (he was replaced as director by Bodkin in 1927); and Barry Egan, head of a Cork firm of goldsmiths and jewellers, who was soon to become a member of Dáil Éireann.

Minister for Finance Ernest Blythe-‘a coinage distinctively our own, bearing the devices of this country’. (George Morrison)

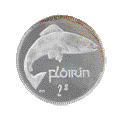

The committee placed newspaper advertisements in July 1926 seeking suggestions for coinage designs from the public, but received few responses. Yeats found the advice of his friends more useful, and, drawing on suggestions from Lady Gregory, Sir William Orpen and Oliver St John Gogarty, he came up with the idea that the coins should portray the products of the country. This idea was endorsed by the committee, which narrowed the theme down to animal products. Their interim report to the minister for finance in August 1926 proposed that ‘the more noble or dignified types’ should be assigned to the higher denominations and ‘the more humble types’ to the lower. Their recommendations started with the horse for the half-crown, followed by the salmon, bull, wolfhound, hare, hen, pig, and finally the woodcock for the farthing. They recommended that the harp should appear on the obverse of all the coins. The committee’s suggestions were supported by the minister, but some reservations were expressed about the pig, and the committee accepted the suggestion that the ram be included as an alternative to the pig in the list of symbols to be sent to artists.

Metcalfe’s designs ‘incomparably superior’

In February 1927 the committee considered designs for the coins submitted by seven artists, three of whom were Irish. The designs submitted by English artist Percy Metcalfe were considered by the committee to be ‘incomparably superior’, and accordingly they recommended that he be commissioned to execute the designs for the coins. Of his two alternative designs for the halfpenny (ram and pig), they chose the pig. Metcalfe’s original designs for some of the coins had to be revised on advice from agricultural experts, and Yeats regretted that ‘the state of the market for pig’s cheeks’ led to the creation of a slimline pig which was ‘better merchandise but less living’. Finally, in April 1928, the committee approved a complete set of trial pieces of Metcalfe’s designs, which were then produced by the Royal Mint in London. They began to be issued to the public on 12 December 1928.

In February 1927 the committee considered designs for the coins submitted by seven artists, three of whom were Irish. The designs submitted by English artist Percy Metcalfe were considered by the committee to be ‘incomparably superior’, and accordingly they recommended that he be commissioned to execute the designs for the coins. Of his two alternative designs for the halfpenny (ram and pig), they chose the pig. Metcalfe’s original designs for some of the coins had to be revised on advice from agricultural experts, and Yeats regretted that ‘the state of the market for pig’s cheeks’ led to the creation of a slimline pig which was ‘better merchandise but less living’. Finally, in April 1928, the committee approved a complete set of trial pieces of Metcalfe’s designs, which were then produced by the Royal Mint in London. They began to be issued to the public on 12 December 1928.

Opening an exhibition of the new coins in November 1928, Finance Minister Blythe pronounced them ‘more interesting and beautiful than any token coinage in the world’. He emphasised that ‘The possession of a distinctive coinage is one of the indications of sovereignty’, an important point in the propaganda war between the government and its republican opponents, who claimed that the Irish Free State was still a dependency of Britain. Thomas Bodkin also spoke at the opening of the coinage exhibition. He explained the committee’s choice of animal designs, stating that, since coins are tokens of a people’s wealth, it was appropriate to show on them the source of that wealth. Bodkin also justified the absence of religious symbols from the coins:

It seemed to me that the placing of religious symbols or the effigies of saints upon our coins would give rise to an unavoidable and most reprehensible irreverence. I saw, in my mind’s eye, a peasant at the fair being paid for a bonham with the image of St Patrick and, impelled by the habit of centuries, to spit upon that image for luck before he rammed it in his trouser pocket. I saw two loafers at the bar of a public house tossing as to which of them should pay for drinks, according as to whether the image of St Bridget or St Columbcille came uppermost.

If Bodkin’s seemingly lighthearted comments on this issue were intended to disarm potential critics, however, he had misjudged those who wished to see religious emblems on the coins. If anything, these comments served to provoke rather than placate.

The coinage debate

By the time the designs were officially released to the public, they had already attracted controversy owing to unauthorised disclosures of the committee’s choice of symbols. The symbols were listed in December 1926 by the short-lived newspaper Irish Truth, which predicted that they ‘will not merely be unpopular, but will be met with positive derision’. Then in July 1927 Percy Metcalfe revealed the symbols to an Irish Independent interviewer, thereby unleashing the first round of criticism in the newspapers and elsewhere.

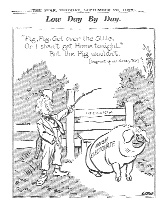

Blythe was asked in the Dáil whether the pig and other farmyard animals were ‘calculated to inspire the public as to the standard of Gaelic culture that National Ireland is striving for to-day’, and whether images reflecting ‘the Christian glories of Ireland’ should not be substituted for ‘designs which are regarded by many people as a travesty on our country’. Blythe stood by the coinage designs, but if he hoped the controversy would soon blow over he was to be disappointed. An even more vigorous debate broke out when the coins were released at the end of 1928.

Blythe was asked in the Dáil whether the pig and other farmyard animals were ‘calculated to inspire the public as to the standard of Gaelic culture that National Ireland is striving for to-day’, and whether images reflecting ‘the Christian glories of Ireland’ should not be substituted for ‘designs which are regarded by many people as a travesty on our country’. Blythe stood by the coinage designs, but if he hoped the controversy would soon blow over he was to be disappointed. An even more vigorous debate broke out when the coins were released at the end of 1928.

While critics of the coinage designs began the debate, the vehemence of the attack quickly provoked a spirited defence. The coins were condemned by their detractors for promoting paganism because they bore no religious symbols; for repudiating the national tradition by neglecting conventional national emblems; for stereotyping Ireland as an agricultural nation; and for putting forward the pig, long associated with the Irish in caricature, as an appropriate symbol of the Irish nation. In reply, defenders of the coins praised their beauty and originality; declared that they were entirely appropriate for a nation whose economy relied so heavily on agriculture; and accused those who wanted religious symbols on the coinage of trying to associate God and Mammon.

‘The wedge of Freemasonry’

Maude Gonne MacBride-the coins were ‘entirely suitable’ for the Free State: ‘designed by an Englishman, minted in England, representative of English values, paid for by the Irish people’. (George Morrison)

The fact that there were no religious symbols on the coins was a major cause of concern for the critics of the designs, who believed that the coins should proclaim Ireland’s status as a great Christian nation. For a number of critics, the absence of religious emblems was no accident but was part of a larger conspiracy to remove religion from public life. Several saw the hands of the Freemasons at work in the coinage designs.

Maude Gonne MacBride-the coins were ‘entirely suitable’ for the Free State: ‘designed by an Englishman, minted in England, representative of English values, paid for by the Irish people’. (George Morrison)

One anonymous critic, identified by the Irish Independent as a priest, wrote:

If these pagan symbols once get a hold, then is the thin edge of the wedge of Freemasonry sunk into the very life of our Catholicity, for the sole object of having these pagan symbols instead of religious emblems on our coins is to wipe out all traces of religion from our minds, to forget the ‘land of saints,’ and beget a land of devil-worshippers, where evil may reign supreme.

Critics of the coins liked to describe them as ‘pagan’, paganism being a more pejorative term for secularism and materialism. As one critic explained, ‘The coins are called pagan in the sense that there is a total absence of a sign that they symbolise the sovereignty of a Christian nation’.

Those who held this view had little time for the argument, advanced by defenders of the coinage designs, that to put religious emblems on coins would be to profane holy symbols. Fianna Fáil’s Nation newspaper thought it ‘strange that Catholics should be so squeamish and puritanical about putting an Irish saint’s image on a thing of common use. According to all Catholic tradition that is where the saints belong.’ Likewise, the Catholic Standard argued that:

If a religious symbol is not to be stamped on a coin because of the possibility of profanity, then there should be no crucifix in a public place, no calling on God to witness in a court of law. For an unbeliever may be guilty of a profanity towards the crucifix, and a perjurer may insult God by calling on Him to witness to a falsehood.

While the critics claimed that the Free State was unusual or even unique among Christian states in having no religious symbols on its coinage, Yeats complained to Bodkin:

I wish they would tell us what coinage seems to them most charged with piety.

To the defenders of the coins, there was nothing irreligious about the animal symbols. The liberal Irish Statesman mocked the coinage critics:

One would imagine that while man was created by God the animal world was created by the devil, so angry are the critics . . . Who would have thought that that poor little hare on the threepenny bit was a form of the devil, or that little woodcock was a demon.

The absence of religious symbols from the coins was a virtue for their defenders, several of whom quoted the biblical verse about rendering unto Caesar what is Caesar’s and unto God what is God’s. The Enniscorthy Echo had no desire to see sacred images associated with the fair, the market and the racecourse:

It is not for Catholic Ireland to suggest or countenance an unnatural union between the Temple and the traffic of the money changers.

‘If Ireland has no other way of proving her religion than by turning her coins into medals,’ concluded the Revd P.V. Higgins, ‘God help her.’

Economics and ideals

A number of critics were angered by the absence of more traditional national symbols, such as the shamrock, round tower and sunburst; Celtic treasures such as the Ardagh Chalice; or historical figures such as St Patrick or Daniel O’Connell. Such symbols, representative of the nation’s long and glorious history, were said to typify ‘all that is noble and elevated’ in Ireland. That the coinage design committee had ignored traditional Irish emblems was not surprising to critics who described the committee’s members as ‘outside the Irish tradition’ or as representing ‘the un-Irish snob mind’.

The committee stood accused of having rejected Ireland’s national ideals because of what was on the coins, as well as what was missing. Critics took umbrage at the apparent suggestion that Ireland’s mission was to be a farmyard, and that its people could do nothing but raise livestock. Moreover, the designs stood for nothing more uplifting than ‘the material idea of eggs and bacon’ or ‘the sordid ideals of commerce, wealth and food’.

Irish Truth was glad the committee had at least restrained itself from decorating the coins with borders of interlacing lines of sausages, or alternating eggs and butter pats. Had the salmon been depicted in the form best known to the public, mused Irish Truth, it would have appeared ‘in three portions decked out with a skewered ticket bearing the legend “3s. 6d. per pound”’.

‘Paddy and the Pig’

Many critics of the coinage designs felt that Ireland’s national dignity had been slighted by the committee’s choice of symbols, and this feeling came out most strongly in reactions to the depiction of a pig and piglets on one of the coins. Pigs had commonly been used in the past by British cartoonists and commentators to represent Irish people as brutish and dirty. It is little wonder, then, that some Irish people were outraged to see the Free State government seemingly approving of the pig as a national symbol. ‘One could easily imagine that an Englishman’s first thought would be to give a permanent domicile to “Paddy and the Pig”’, one critic wrote, ‘but to find Irishmen so devoid of all national feeling as to accept so calmly such degrading designs is amazing!’ To Archdeacon J. Fallon, the pig was associated with ‘wallowing in the mire, and our greatest enemies could not offer us a bigger insult than to represent this as one of our grand ideals’.

At least one supporter of the coinage designs was prepared to leap to the pig’s defence. A small farmer from Mayo saw ‘this interesting and useful little animal’ as ‘the poor man’s friend… The pig is on our breakfast table, at dinner, too, and in our pockets in the shape of good banknotes.’ This farmer welcomed the appearance of animals on the coins, ‘for they are surely my friends. Idealists may say I am materialistic, but as long as I have bacon and eggs for breakfast they can have their ideas.’ Others pointed out that the nation as a whole relied on the animals depicted on the coins. Since these animals were the principal source of Ireland’s wealth, it was entirely appropriate that they should appear on the coins.

Defenders of the coins believed that, far from diminishing Ireland’s national dignity, the coins could be a source of national pride because of their beauty. The objections to the coins were themselves likely to tarnish the nation’s reputation, in the view of the Irish Statesman, making Ireland appear ridiculous:

What next will happen to proclaim to the world the supreme delicacy of the Irish soul? Will the Department of Agriculture be attacked because it sanctions very loose relations between bulls and cows? One bull, one cow! Will that be the next slogan? These fanatics are going to make Ireland the jest of the planet.

The king’s head

Veteran republican Maude Gonne MacBride declared that the coins were ‘entirely suitable’ for the Free State: ‘designed by an Englishman, minted in England, representative of English values, paid for by the Irish people’. However, while republicans like Gonne MacBride claimed that the Free State was a colony of Britain, the Free State government was keen to accentuate the state’s independence. In line with the government’s Gaelic revivalist ideals, the Irish language alone was used on the coins (the proper Irish title of the state, ‘Saorstát Éireann’, appeared on the coins, whereas the stamps gave their country of origin as ‘Éire’).

Even more importantly, the king’s head did not appear on the obverse of the coins, despite the fact that the Free State was part of the British Commonwealth of Nations, with a governor-general representing the British monarch as head of state. Instead, the obverse bore the uncrowned harp (modelled, like that on the Great Seal of the Irish Free State, on the ‘Brian Boru’ harp from Trinity College, Dublin). In 1913 Patrick Pearse had written that ‘A good Irishman should blush every time he sees a penny’ because the royal features on the obverse were a reminder of ‘the foreign tyranny that holds us’. Fifteen years later, the independent Irish state, which traced its origins to the actions of Pearse and his comrades in the Easter Rising, became the only self-governing dominion within the British Commonwealth to remove the king’s head from the state’s coinage.

There was remarkably little mention of the removal of the king’s head from the coins amid all the discussion about the designs. Presumably most people in the Free State regarded the issuing of a coinage that did not bear an image of the king as such a natural development that it was not even worth remarking on. While those who had been unionists before the creation of the Free State no doubt regretted the disappearance of the old coins, there was little expression of such sentiment in the newspapers. Nor did commentators on the coinage designs show any interest in what people in Northern Ireland might think of them, despite the fact that the coins were frequently described by such commentators as representing ‘Ireland’ rather than the Irish Free State. The failure to place the king’s head on the coins did not go unnoticed by unionists in Northern Ireland, however. This was just one of a number of symbolic assertions of the Free State’s separation from Britain which were regularly cited by unionists as reasons why ‘loyal Ulster’ could never agree to a united Ireland. Unionists were not prepared to give up their king’s head for a horse (or a harp).

Contention and consensus

The coins were condemned by their detractors for putting forward the pig, long associated with the Irish in caricature, as an appropriate symbol of the Irish nation.

The lack of objection within the Free State to the absence of the king’s head from the coins shows that, despite the considerable controversy over the coins, there were areas of underlying consensus. Defenders and critics of the coinage designs also shared two key concerns on which the debate focused: the place of religion in public life, and the achievement of national dignity and self-respect. Critics of the coins believed that a Christian nation should acknowledge God on its coinage. They saw the failure to do so as a deliberate rejection of God that reflected badly on the nation. Some defenders of the coins, however, preferred to see God kept apart from both Caesar and Mammon. They, too, wanted the state to follow Christian principles, but reminded ‘Catholic Ireland’ of the dangers of inviting the money-changers into the temple. As for the concern with national dignity, this was a product of political and cultural insecurity in a new state that had not yet fully achieved either political stability or separation from Britain. Those who took offence at the designs on the coins wanted symbols that would display to the world Ireland’s idealism and the grandeur of its civilisation. Defenders likewise wanted coins in which they could take pride, and believed that the beauty of Metcalfe’s designs would enhance Ireland’s international reputation.

The coins were condemned by their detractors for putting forward the pig, long associated with the Irish in caricature, as an appropriate symbol of the Irish nation.

The passions aroused by the coinage debate may have something to do with the deep ambivalence that many people feel about money. Underlying the arguments about the appropriateness of putting religious symbols on the coins was a difference of opinion about money itself, and about whether it was right to associate religion and commerce. Both sides in the debate agreed, however, that the design of coins was no insignificant matter. To participants in the debate, coins were indeed ‘silent ambassadors’, not only of national taste but also of the nation’s moral, economic and cultural aspirations.

Ewan Morris is a research and policy officer at the Council for International Development in Wellington, New Zealand.

Further reading

B. Cleeve (ed.), W.B. Yeats and the designing of Ireland’s coinage (Dublin, 1972).

E. Morris, Our own devices: national symbols and political conflict in twentieth-century Ireland (Dublin, 2004).

M. Moynihan, Currency and central banking in Ireland, 1922–60 (Dublin, 1975).