D. A. Chart 1878–1960: Archivist, Historian, Social Scientist

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 1 (Spring 2003), Volume 11Our neglect and ignorance of some important figures in early twentieth-century Ireland were highlighted recently during the transcription and publication of the Heads of Household Index to the 1851 census of Ireland for Dublin City compiled by D.A. Chart. In the light of the destruction of nineteenth-century Irish census returns housed in the Public Records Office (PRO) at the Four Courts, Dublin, in June 1922 at the start of the Civil War, Chart’s index was the only comprehensive nineteenth-century source for the hard-pressed genealogist. But who was Chart? He turns out to have been a very interesting and important figure, an enthusiastic historian and archivist who made a major contribution to the cultural and intellectual life of the whole island of Ireland.

Out of sympathy with the new regime

No doubt his most important contribution was as Deputy Keeper of the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) from its inception in 1924 until his retirement in 1948. Being out of sympathy with the new regime in the Irish Free State, Chart had been transferred from the Public Records Office in Dublin—initially on loan, made permanent from April 1922—to the new administration in Belfast. A brief entry in the 55th Deputy Keeper’s Report, PRO, noted the move: ‘On the application of Sir E. Clarke, Mr D.A. Chart, an administrative officer, who was allowed to go to Belfast on loan in March, was transferred to the Ministry of Finance, Northern Ireland, as from 1 April, 1922’. He was one of 300 Irish officers in Dublin who volunteered to go north. He was made Principal in Finance, a significant promotion and a good career move, whatever else the motivation might have been. When the new PRONI was established, he was appointed its first Deputy Keeper on 14 January 1924.

Chart had joined the Public Records Office in 1902, having successfully sat the competitive higher civil service examination. Although born in Lucknow, India, on 13 October 1878, he was educated in Kilkenny College and Queen’s College, Cork, where he was awarded a BA in classical studies in 1899, and an MA in history and political science in 1904. He married Lily McCotter, daughter of William McCotter and fourteen years his senior, in St Joseph’s Catholic chapel in Cork on 15 July 1903. He is described as a ‘clerk’, son of David Chart, a hotel-keeper of 8 Annadale Park, Clontarf, Dublin. They lived at 37 Belgrave Square, Dublin, according to the 1911 census.

‘God’s bounty’

From 1906 to 1912 Chart worked in the State Paper Office in Dublin Castle and calendared the late eighteenth-century state papers. From 1912 to 1915, and again from 1918 to 1921, he was in charge of the Public Search Room in the Four Courts, where he worked on the Exchequer Rolls. In 1915 he compiled the Heads of Household Index to the 1851 census for Dublin City because of the excessive workload on staff in the PRO searching for proof of age for applicants for the old-age pension, recently introduced by the chancellor of the exchequer, Lloyd George. It could be claimed by applicants aged 70 years or more, and was referred to as ‘God’s bounty’ by the grateful recipients. In the absence of adequate records of birth, it is noted in the PRO’s Deputy Keeper’s Report 47 (1915) that the census returns of 1851 have been useful in furnishing proof of old age . . . [therefore] . . . a catalogue of families residing in Dublin on the night the census was taken has now been compiled from the census returns—and will be used henceforth to check the statements of applicants and to locate families living in Dublin of whose address there is no certain knowledge. The catalogue has been prepared by D.A. Chart; it will save the Dublin census returns from much unnecessary wear and will be extremely helpful to genealogists, claimants of OAPs, etc.

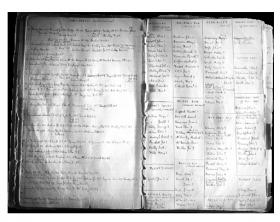

One of Chart’s two original hand-written ledgers of Heads of Household Index to the 1851 census of Ireland for Dublin City. (Hugh Glynn)

At the time it was probably not Chart’s most important work. However, with the destruction of the PRO in 1922, the catalogue or index remains the only comprehensive record of families living in Dublin City for the whole of the nineteenth century, in fact up to the 1901 census, and so constitutes an important source for modern researchers.

Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland

His compilation of the index illustrates Chart’s particular interest in economic and social history. During his period in Dublin he was a council member of the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland and contributed a number of articles in this sphere to its journal. He sympathised with the situation of the poor Dublin working class and described their conditions in two articles: ‘The general strike as a labour weapon’ and ‘Unskilled labour in Dublin—its housing and living conditions’. ‘The general strike’ was written a year before the events of 1913. He expresses concern at the conditions of unskilled labourers, as the class most likely to be forced to use the weapon of the general strike, which invariably fails. He claims that there was ‘no exaggeration in the statement that the people of this class are perpetually on the verge of hunger’. He recommends intervention to improve the deplorable state of industrial relations and the setting up of a system of compulsory arbitration and conciliation courts, an idea ahead of its time. He is even more outspoken in ‘Unskilled labour’, written just after the 1913 lockout. He examines ‘the family life of the Dublin unskilled labourer receiving an average weekly wage of 18/-’, and finds them ‘badly housed, ill-fed, unhealthy, indigent, struggling, hopeless’. Despite this sombre picture he pays tribute to the ‘Dublin character’:

The Dublin labouring class possesses several fine qualities. It is deeply religious . . . [and] . . . lives, as a rule, a much more moral and respectable life than could be expected considering its surroundings. It exhibits in a marked degree the social virtues of kindness, cheerfulness, and courtesy. Mentally and morally this class is probably on a higher level than the working class of most cities.

He chides the labourer for accepting the situation ‘as his natural lot’. He recommends increasing the wages of unskilled labourers to a proper living level. Padraig Yeates, who describes Chart as a social scientist, quotes from these articles in his recent excellent study of the 1913 lockout. Chart took practical steps to help improve the slum situation in Dublin. He was involved with an experimental model flat scheme in Gardiner Street and its associated boys’ club. While Chart could no doubt be considered a member of the establishment, his views on social matters were in conflict with the established order of things.

With the destruction of nineteenth-century Irish census returns housed in the Public Records Office at the Four Courts, Dublin, in June 1922 at the start of the Civil War, Chart’s index was the only comprehensive nineteenth-century source for the hard-pressed genealogist. (George Morrison)

No doubt this stance was supported by his study of Irish economic and social history, which is illustrated by two other articles, ‘A study of Irish economic history’ and ‘Two centuries of Irish agricultural statistics—a statistical retrospective’, and by some books. He wrote An economic history of Ireland, seeing the lack of suitable texts when he was an examiner for the Irish Intermediate Education Board. Ireland from the Union to Catholic Emancipation is a study of the social, economic and administrative conditions of the time. He contributed The story of Dublin to the Mediaeval Town Series published by Dent in 1907. He edited Vol. XI, The marriage entries for the registers of the parishes of St Andrew, St Anne, St Audeon and St Bride, 1632–1800, for the Parish Register Society of Dublin in 1913. He was elected a member of the Royal Irish Academy and appointed an inspector of the Historical Manuscripts Commission in the same year. Chart was an active member of society in Dublin at this time, as he was later in Belfast, and contributed to many charitable and philanthropic organisations. He was awarded a Litt.D. in 1922 by Trinity College, Dublin, in recognition of his work.

Public Records Office, Northern Ireland

In Belfast Chart set about establishing a new Public Records Office for the new state. He had the advice of Radcliffe, Assistant Keeper PRO, London, who had experience of Irish records, to assist him. He assembled a small staff, ‘all of which, with the exception of one, has experience in the PRO of Ireland’, according to his first report as Deputy Keeper. He was fortunate that

probate registries and Crown and Peace offices contained an accumulation of documents which were aged over twenty years from the date of making, awaiting transfer, partly from the disturbances of customary routine due to war conditions, partly from motives of prudence owing to the disturbed state of the country, which made transport unsafe; these documents had not been transferred to Dublin.

He took possession of records from the Belfast Registry and the Armagh District Registry, and the Crown and Peace records from Antrim, Armagh, Fermanagh and Londonderry. The destruction of the Four Courts PRO in 1922 must have been a hard blow for Chart, having spent the previous twenty years caring for the precious records. He did his best to repair the damage done as Deputy Keeper, PRONI, especially for the Six Counties, which came under his remit:

In view of the enormous destruction of records in Dublin efforts were made to obtain copies of the destroyed documents from every possible source, and concurrently with the steps taken to obtain original documents, communications were addressed to government departments, solicitors, and private persons in whose hands such copies were likely to be found.

From 1906 to 1912, Chart worked in the State Paper Office, in Dublin Castle’s Record Tower, and calendared the late eighteenth-century state papers. (Brigid Fitzgerald)

In the absence of primary material he was forced to rely on estate papers, family papers, legal papers from law firms, business records, etc.—what would under normal circumstances be considered supplementary or secondary sources—to stock his archive. He got a ready response—indeed, many from sources in the South. Chart’s pioneering work in this field has proven to be a rich and valuable source. According to K. Darwin, many local archives throughout the United Kingdom followed Chart’s initiative. Chart was responsible for setting up and developing the PRONI in its formative years, and we owe much of the now highly developed state of that institution to Chart and his staff.

Publications

Chart continued to publish in Belfast, contributing to many learned journals and producing descriptions of many important collections: Londonderry and the London Companies (1928) is based on the seventeenth-century Phillips survey of County Londonderry; The Kelsey Papers (1929) concerns the early history of the seventeenth-century exploration of Hudson Bay and vicinity in Canada from the family papers of Major A.F. Dobbs; The Drennan Letters (1931) is from the correspondence of William Drennan MD, founder of the United Irishmen, with Martha and Samuel McTier, his sister and her husband; and The Register of Primate John Swayne, archbishop of Armagh, 1418–1439 (1935). He wrote a History of Northern Ireland, again from the industrial and economic point of view. From 1929 to 1957 he was a member of the Historical Manuscripts Commission. From 1944 to 1959, the year before he died, he was also a member of the Irish Manuscripts Commission, acting as the link between the two bodies, a position in which he took great pride and satisfaction.

If this was not enough, as Principal in Finance he also had formal duties in connection with administration of the Ancient Monuments Act (Northern Ireland) of 1926. His pioneering initiatives included the use in the late 1920s of aerial photography for archaeological purposes and the editing in 1941 of A preliminary survey of the ancient monuments in Northern Ireland, which laid the foundation for post-war advances. He was vice-chair of the Ancient Monuments Advisory Committee from 1925 to 1948. His interest in history and architecture led to his becoming a founder member of the Northern Ireland branch of the National Trust in 1937.

Chart married twice. His first wife, Lily, died in 1935. He married Florence Blair in 1941 in Belfast. Darwin describes him as a kind and tolerant man with an imposing physical presence and an indefatigable enthusiasm for his work. Other interests, outside his wide professional career, included music and a strong devotion to the Church of Ireland. He retired as Deputy Keeper in 1948, but retained many of his interests until his death on 9 December 1960, at the age of 82.

Seán Magee is a Dublin researcher specialising in family history.

Further reading:

S. Magee (ed.), 1851 Heads of Household Census of Dublin City (Dublin, 2001).

P. Yeates, Lockout: Dublin 1913 (Dublin, 2000).