Archaeology and war in an Irish town

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, General, Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2009), Volume 17

Post-medieval artefacts recovered during archaeological excavations in Derry in the 1970s

In 1974 the recently established Institute of Continuing Education at Magee College—arising out of the ashes of the New University of Ulster débâcle—earnestly sought a role for itself. Cross-community activity became highly valued and, despite its destabilising possibilities, local history was identified as a suitable arena for these endeavours. Consequently Derry City Council established a workshop to investigate the origins of the city and the university agreed to create a job to develop the subject. The author was appointed to that post.

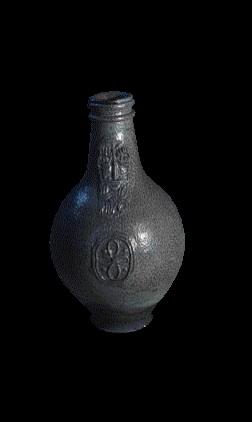

Londonderry Corporation had established a Civic Museum in 1903. Commandeered during the Second World War, it never recovered and finally closed in 1951. One well-known archaeological object from the city—a seventeenth-century German Bellarmine pot that mocked the famous, allegedly pot-bellied, Counter-Reformation cardinal—had been found in the 1930s at the bottom of a well on the site for an extension to the Apprentice Boys Memorial Hall, the main Protestant institution in the city. The author set out to find this ‘Holy Grail’ but failed. Only one possibility remained—maybe it was still in ‘The Mem’. Despite my southern, Catholic and nationalist background, I was welcomed to the hall and found the pot in its rarely visited attic.

Meanwhile, the IRA and city planners had ripped apart the physical fabric of the city. By the early 1970s redevelopment had commenced in Fountain Street, the heart of Protestant Derry. The Victorian terraced houses had been built on top of the filled-in seventeenth-century external town ditch. In fact, the excavated earth from the ditch was buried inside the skin-deep ‘stone’ walls. I soon became a regular visitor to the area, searching through the JCB spoil-heaps for the scraps of pottery thrown into the ditch by the seventeenth-century citizens. The ditch had clearly been used as a ‘dump’ in the peaceful times between the sieges of 1649 and 1689.

Bombs, bomb-scares and riots

Bellarmine pot, found in the 1930s on the site for an extension to the Apprentice Boys Memorial Hall.

In 1975 the author began a programme of rescue excavation in the centre of the bomb-damaged city. We continued that work in one form or another until 1984. Apart from the bombs, bomb-scares and riots, there were occasional gun-battles nearby, and on one occasion shots were actually fired at members of the excavation team—‘over the heads’ was the admission at the subsequent court case. Arrests of members of the team were frequent, including one in which my own work gloves were found to have been in contact with a suspicious substance (an occupational hazard when working on recently cleared bomb sites). Nocturnal break-ins by the army to our site huts—located in an otherwise largely deserted city centre—were commonplace. Despite the distractions, we managed to investigate a relatively large number of sites. Although the disturbed urban stratigraphy made interpretation difficult, we were able to recover many hundreds of thousands of objects—mainly potsherds and pieces of clay tobacco pipes, as well as evidence for more substantial features. We discovered a number of wells inside the walls, some of which had seventeenth-century and later objects at their bottoms, and two seventeenth-century houses in Linenhall Street—surviving partly inside the fabric of later buildings. We also excavated a number of sections of the town ditch.

Perhaps the greatest paradox was that, having survived all that the Troubles could throw at us out in the city, the post-excavation research suffered a devastating blow in the calmer refuge of Magee College when, following the establishment of the University of Ulster in 1986, the university authorities moved collections of artefacts and excavation archive without supervision, causing tremendous damage and loss. It is only now, after more than twenty years, that an attempt can be made to rescue something from that disaster.

Archaeology and conflict

Archaeology is no stranger to sites of ethnic and religious conflict. Many of the most important sites associated with the Bible and the ancient civilisations of the Near and Middle East are located in traditional conflict zones. During the Hunger Strikes in the 1980s, protesters used a JCB to carve a huge ‘H’ across the Bronze Age stone circles at Beaghmore, Co. Tyrone, apparently for no other reason than that the site was government-owned. A UNESCO conference is being held this year in Vienna on ‘Archaeology in Conflict’—specifically dealing with issues of ‘cultural cleansing’. The manifesto for the conference argues that:

‘The protection of cultural heritage is not merely about monuments and artifacts but about people and identity. Consequently, preserving cultural heritage is not about the past but concerns the present and future of humankind.’

In 1616 the Londoners presented the so-called State Sword to Londonderry, then under construction. On the pommel is inscribed the word ‘Londonderre’—no final ‘y’. It appears that this was an attempt to render the sound of the Irish name, Doire. The walled city and its archaeology is one of Ireland’s great inheritances. It is marvellous that it is at last receiving the sort of attention it deserves. HI

Brian Lacey, an archaeologist and early medieval historian, is CEO of the Discovery Programme.

State Sword pommel, inscribed ‘Londonderre’. (Derry Heritage and Museum Service)

Further reading:

B. Lacey, ‘Two seventeenth century houses at Linenhall Street, Londonderry’, Ulster Folklife 27 (1981), 52–62.

B. Lacey, ‘The development of Derry, 600–1600’, in G. Mac Niocaill and P. F. Wallace (eds), Keimelia: studies in medieval archaeology and history inmemory of Tom Delaney (Galway, 1988).

B. Lacey, Siege city: the story of Derry and Londonderry (Belfast, 1990).

B. Lacey, ‘The archaeology of the Ulster plantation’, in M. Ryan (ed.), The illustrated archaeology of Ireland (Dublin, 1991).