A Scrapping of Every Principle of Individual Liberty

Published in 20th Century Social Perspectives, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 4 (Winter 2000), Volume 8

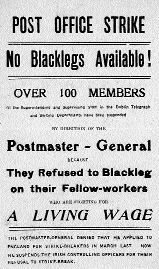

September 1922-striking postal workers pose for the camera. (Irish Labour History Museum)

The unemployment is acute. Starvation is facing thousands of people. The official Labour Movement has deserted the people for the fleshpots of the empire. The Free State Government’s attitude towards striking postal workers makes clear what its attitude towards workers generally will be.

Thus wrote Liam Mellows, IRA director of purchases, from his prison cell in Mountjoy Jail in September 1922, several weeks before his execution by the provisional government of Saorstat Éireann. The significance of this seminal incident, the first trades dispute faced by an Irish government, was not lost on Liam Mellowes or his contemporaries. Yet despite the fact that the strike, and the government’s response to it, clearly exposed the inherent antagonisms between a nationalist bourgeoisie and an organised proletariat, it has virtually gone unrecorded in the history books, overshadowed by the national obsession with the details of the Civil War which was still raging at the time.

The story of the postal workers’ strike can be pieced together, however, from the records contained in the Postal and Telecommunications Workers Union archive, held in the Irish Labour History Museum. An examination of the twenty-two union files concerning the strike and its aftermath reveals a narrative of high drama that centred around the issue of the right to strike.

The strike was provoked by the provisional government’s attempt to cut the ‘cost of living’ bonus, which was paid on a twice-yearly basis to all civil servants, including postal workers. Throughout the Great War civil servants in Britain and Ireland had been granted an allowance to shore up their wages against the dramatic inflation of the war years. After the war these allowances were retained as ‘cost of living’ bonuses to off-set against continuing rising prices. The government took the inflammatory step of introducing a cut in the bonus as early as March 1922, with the threat of further cuts to come. An emergency resolution issued in response by the Irish Postal Union pointed out that:

Whereas the majority of the Irish Civil Service recently gained substantial additions to their permanent remuneration, the wages of the Post Office staff are on practically the same level as those of thirty years ago. Any further reduction will bring Post Office wages to starvation level.

The union resolved to take ‘the necessary steps for an immediate withdrawal of labour in the event of a reduction being enforced’.

The Douglas Commission

Consequently the government agreed to the setting up of an independent commission of inquiry into wages and working conditions within the postal service, chaired by J.G. Douglas. Its interim report in May 1922 concluded that the cuts could not be borne by postal staff in the lower grades without serious hardship. It recommended instead that certain levels of wages in the postal service be immediately increased, and that any further cuts should be postponed until an Irish cost-of-living index was agreed upon, or until the commission produced its final report. The government, however, ignored the findings and drew up a cost-of-living index based on what the unions alleged were false figures. On the basis of these controversial figures further cuts were announced, to be put into effect in September 1922. ‘In other and plainer terms’, as an article in Voice of Labour, official organ of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, pointed out, ‘a man who, in the opinion of the commissioners, could not reasonably bear a reduction of ten shillings in May, is deprived of fifteen shillings in September’.

The three unions representing postal workers, the Irish Postal Union, the Irish Postal Workers’ Union and the Irish Post Office Engineering Union, were left with no option but to call for a strike. In anticipation of such action the Postmaster General, James J. Walsh, issued a ‘special notice to the staff’ on 6 September 1922, stating:

In view of threats which have been made by sections of the staff to withdraw their labour because of the application of the Irish cost-of-living figure to the civil service bonuses, all civil servants should note that:

1) An officer withdrawing his labour automatically forfeits his position, and

2) In the event of subsequent reinstatement on settlement, reinstatement would not carry with it restoration of pension rights for the previous service or of continuous service.

by command of the Postmaster General

The three Postal Unions came together on a temporary basis to form the United Postal Union, which promptly wrote to Thomas Johnson, secretary of the Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Congress, pointing out the intimidatory nature of the special notice. This letter (7 September 1922) refers to

the bullying of his workers by a member of the government into dropping legitimate trade union methods of redressing their grievances. There is, indeed, an attempt to deny the right of government workers to be members of trade unions.

Right to strike

This was, in fact, precisely the stand taken by the government. The Voice of Labour commented:

The government was appointed last Saturday afternoon. At the time previously appointed, namely, 6pm on Saturday, the strike began…The first act of the government was to issue on Saturday night the following proclamation:

The government does not recognise the right of civil servants to strike. In the event of a cessation of work by any section of the postal service, picketing, such as is permitted in connection with industrial strikes, will not be allowed.

The workers in general, and Trade Unionists in particular, will not be silent. The right to strike is in danger and it must be defended.

When the women and men of the postal service withdrew their labour on 10 September, the police and military were ordered to take whatever action they deemed necessary to remove pickets from the streets. Initially the police carried out this onerous task with restraint, and at least one officer was dismissed for refusing to arrest peaceful pickets on the grounds that he was unaware of any law they were breaking. (Despite appealing his dismissal, the officer was never reinstated.) As the strike continued and the military were called in, however, more brutal tactics were employed against the strikers.

The government’s refusal on the Saturday to recognise the postal workers’ right to strike was followed by a Dáil debate on Monday 11 September. The majority of the supporters of the government voted against the right of government employees to strike, as did the farmers’ representatives. The Labour Party deputies and some independents voted in favour of the right to strike, but they were in a minority. The Voice of Labour listed the deputies who voted for and against by name and declared:

The government has raised the issue above an ordinary wages dispute—it has raised it to the higher level of the right to strike and the right to picket. It is an issue and a challenge which the trade union movement cannot afford to ignore.

Members of the Free State Army dressed in civilian clothes were already acting as strike-breakers, sorting post and delivering letters, and military escorts were being provided around the country for civilian blacklegs. An undated statement issued by the joint strike executive claimed that:

Teachers and managers of certain city schools have been asked to supply lists of applicants for Post Office employment—in other words for blacklegging. Will they do so, or will the parents consent to have their children branded by the Free State government with the stigma of juvenile slaves? We shall see. We have the most reliable information that one or two notorious ex-members of the Black and Tans are at present in the service of the PMG [Postmaster General] in Dublin. In more than one instance ex-officials of the Post Office dismissed and imprisoned for theft of correspondence have been re-employed since the strike, and have now access to all kinds of public property in the Post Office.

Early yesterday morning an armoured car (no. L13) made frequent and deliberate attempts to run down the pickets at the front and rere of the Rink sorting office.

Press censorship

This kind of statement from the joint strike executive was the forerunner to a strike bulletin which the unions began to issue on a daily basis in response to unfavourable press coverage. That a form of press censorship was in operation became clear when an advertisement favourable to the strike which was tendered by the Irish Women Workers’ Union was refused by the Evening Herald, although it was eventually published by the Daily Telegraph. The strike bulletin typically contained accounts, for instance, of how unemployed men around the country were being warned that they would lose their unemployment benefit if they refused to take up scab work in the Post Office. A letter published in the bulletin from a political prisoner in Mountjoy stated that the governor had offered release to any men who were prepared to blackleg.

Issues arising from the strike continued to provoke heated debates in the Dáil. On Wednesday 13 September 1922 Labour deputies Thomas Johnson and Cathal O’Shannon both expressed their concern over the infringements of civil liberties resulting from the government’s handling of the situation:

We are here raising the question that we are raising, because of its effect on the general labour movement, and because of its effect upon the carpenter, the docker, the shop assistant, and every other worker at any other time. You are laying it down that military can disperse a picket, that military can fire at a picket or over the heads of a picket; that military can use terroristic methods to destroy a body of workers carrying on what I contend to be a legal operation…Is that the state of affairs to which we in Ireland have come at this day, that this government and this parliament find that the very first act of its ministry is an act of such a nature that all these things flow from it, that there is a scrapping of every principle of individual liberty?

The postal strike was rapidly becoming central to the whole question of where the Irish Revolution was going. The struggle for national independence had been, apparently inextricably, bound up with the struggle for social revolution, as embodied in the figure of James Connolly. The overthrow of the ruling classes by the Bolsheviks in Russia had impacted hugely on the ideology of the Republican movement while the battle against the foreign oppressor continued.

The Central Telegraph Office, Amiens street being closed in consequence of the officials’ strike. A large picket stationed here was placed under arrest after having been warned to disperse’. (Freeman’s Journal, 12 September 1922)

In the aftermath of the achievement of the nationalist goal, however, the rift between those who supported the Treaty and those who were still holding out for the establishment of an independent republic was not the only division to manifest itself; those who had believed that they were fighting for a new order based on socialist principles were now compelled to face the bitter truth that the revolution had betrayed them. An article published in the Voice of Labour during the strike stated this new perception clearly when it concluded:

The peaceful evolution of the Free State will mean the triumph of the landlord, large land-holding and big commercial classes. The orthodox politicians who have become the custodians of the republican principle have moved far from the policy of Connolly; they are neither qualified nor disposed to cut adrift from the environment or convention of graft and profit in which they were conceived and into which they were born as a party.

Woman shot on picket duty

On 17 September 1922 one of the most dramatic incidents of the strike occurred when Miss Olive Flood was shot at close range and wounded by a Free State soldier while she was on picket duty in Merchant’s Arch, Dublin. The reporting of this event in the Irish Independent was rejected by the strike executive who issued a statement:

Today’s newspaper account of the wounding of Miss Flood, telephone operator, is clearly that supplied by the military. The union’s account of the incident was almost entirely suppressed.

The newspaper report claimed that, while shots had been fired into the air, Miss Flood’s injury had been caused by a small piece of falling masonry dislodged by a bullet. The union’s version of the incident was very different. According to statements from those who had been present at the scene, the soldier had ordered the pickets out of the arch at gunpoint. As they began to move away he fired, and shot Miss Flood in the back. She was rushed to Jervis Street Hospital where it was discovered that the bullet had been deflected by a suspender buckle, so that she sustained only a flesh wound. Discretion would, no doubt, have contributed to preventing a more detailed discussion of the shooting of Miss Flood in the newspapers, given the delicate nature of her injury. Nonetheless, the shooting of a woman picket by Free State troops in the course of an official trades dispute caused outrage amongst the public in general, and increased support for the strikers.

Postmaster General had once promoted ‘Bolsheviki literature’

A range of methods of undermining the strike were pursued at the instigation of the Postmaster General, James J. Walsh. Walsh, a former postal worker himself, had been an active member of Sinn Féin for several years, and had been one of the men responsible for the arrangements for the inauguration of Dáil Éireann. He had a reputation for radicalism, and early in 1919, as a method of provoking unrest amongst British soldiers stationed in Ireland, he had urged Sinn Féin to ‘disseminate Bolsheviki literature to the military in this country’. As a minister in the new government, however, he was determined that nothing should interfere with the establishment of a successful independent Irish State, and used his power ruthlessly to crush the postal workers and make an example of them. An article in the strike bulletin commented:

Mr. J.J. Walsh was once a prominent trade unionist. He waved the Red Flag in Liberty Hall some years ago. Strikes he then regarded as a meek and mild weapon. Nothing less than revolution would satisfy him. He is now a cabinet minister with £1,700 a year [Postal workers at this time were earning, on average, approximately £200 a year].

Later in the twenties, when Walsh had become director of elections for Cumann na nGaedheal, a journalist who arrived to interview him in his office was confronted with the spectacle of Walsh distributing brass knuckle-dusters to election workers.

An incident that was typical of Walsh’s methods occurred in Limerick on 28 September 1922, the penultimate day of the strike. A Free State army officer dressed as a woman, in skirt and shawl, attempted to pass the picket at the Enquiry Office. When addressed by a striker the officer, armed with a knuckle-duster, punched the man in the face. This was the signal for a general attack on the picket by about twenty soldiers. Revolvers were produced but no shots were fired. Instead the pickets were pistol-whipped. Fifteen strikers were seriously injured in this attack, five of whom were women.

Hardship and hunger

The striking clerks, postmen, sorters, telephonists, messengers, cleaners, patrolmen and engineers suffered considerable financial hardship while the dispute continued. Two cuts in the cost of living bonus meant that workers’ salaries had been dramatically reduced, while prices continued to rise. Now, with no wages at all and a limited strike fund, the postal unions turned to Congress and the Labour Party for assistance. They were advised to approach other unions on an individual basis.

Johanna Kelly (1833-1929), here aged sixty, arrived on the Panama 12 January 1850 and later married John Bushell.

Ironically, the efforts of other unions to help the strikers were often seriously hampered by the effects of the strike. The Railway Clerks Association of Great Britain and Ireland sent their contribution to the strike fund in late October, apologising for the delay and explaining that the appeal for financial assistance issued by the joint postal unions had not reached their head office in London until the last day of the strike, due to the dislocation of the strike itself.

Alongside hardship and hunger, the postal workers had to contend with constant accusations of betraying the cause of national independence. A statement issued by the executive pointed out that

The members of the government thought it was patriotic for the Post Office staff to go on strike on behalf of the Mountjoy hunger strikers and on the occasion of the Mountjoy executions, while the Chamber of Commerce then called us unpatriotic. Now, when we withdraw our labour for ourselves and our families, both parties call us unpatriotic.

The strike as a political weapon against a colonial administration had had the full support of the Sinn Féin party prior to independence; now that Sinn Féin was in power the use of the strike as a means for workers to protect their standards of living was perceived by the government as an unacceptable threat to the stability of the state. It was becoming increasingly obvious to the labour movement in Ireland that a native government based on privilege was at least as inimical to the interests of the working people as a foreign one had ever been. A leading article published in the Voice of Labour on 23 September 1922 remarked:

A foreign flag generally, perhaps invariably, denotes slavery, but national independence and a national flag do not inevitably or invariably denote human freedom.

Eventually the strike came to an end on 29 September 1922, with a commitment from the government that the Douglas commission would proceed with further investigations into pay and conditions for postal workers. The United Postal Union issued a resolution on 2 October:

That with a view to presenting a common front to the Department at the final sittings of the Commission, and for the purpose of facilitating the issue of the final report before December 1st, the executives of the Irish Postal Union, the Irish Postal Workers’ Union and the Irish Post Office Engineering Union, agree to provisional amalgamation; the question of permanent amalgamation to be discussed by special conferences of each union, as early as possible after the final report of the commission.

In fact the IPU and the IPWU agreed to permanent amalgamation in 1923, when they became the Post Office Workers Union, but the IPOEU remained separate until 1989 when a merger resulted in the establishment of the Communication Workers’ Union.

Victimisation

In a meeting with members of the Labour Party on 25 September 1922, President Cosgrave had given assurances that no victimisation of strikers would take place on settlement of the dispute. As soon as the strike was declared over, however, J.J. Walsh, the Postmaster General, dismissed the meeting with President Cosgrave as ‘informal’, thus invalidating any exchanges which had occurred. Walsh then proceeded to implement the most vicious methods of victimisation available to him.

Striking postal workers protest at harassment of pickets. (Irish Labour History Museum)

Experienced workers who had supported the strike were withdrawn on the grounds of trumped-up charges of incompetence and replaced by untrained staff who had been drafted in as strike-breakers; these same individuals who had provided scab labour throughout the strike were given permanent appointments without having to undergo the requisite medical and educational examinations; those refugees from the pogroms in Belfast who had been offered appointments in Dublin if they took up duty in the Rink sorting office during the strike and had refused, were forced to return to Belfast.

The hardest blow, however, was the government’s decision to regard the strike as a break in service affecting pension rights and incremental rates. In a letter to J.J. Walsh dated 5 May 1924 William Norton, general secretary of the POWU, wrote:

In 1920 when my union struck as a protest against the treatment of the Mountjoy hunger-strikers, its action was applauded and approved by the then leaders of the Sinn Féin party, who in many cases are now members of the government. From the point of view of the British administration the strike of its employees at that period had a grave political significance, and was, no doubt, viewed seriously. The only punishment, however, which was inflicted on my members was the stoppage of pay for the two days’ absence.

My Executive desires me to contrast this decision of the then much maligned British administration with the action of the present administration on the occasion of the strike of 1922 in deferring increments, and to express regret that a native administration should be guilty of such vindictiveness and such hostility to trade union action.

Despite the constant efforts of the union, however, it took ten years before the incremental rates were restored and two more years before the issue of pensions was resolved. The 1922 strike and its aftermath seemed to bear out the truth of James Connolly’s vision of the consequences of a nationalist revolution divorced from socialist principles:

‘Let us free Ireland’ says the patriot who won’t touch socialism. Let us all join together and cr-r-rush the br-r-rutal Saxon. Let us all join together, says he, all classes and creeds. And, say the town workers, after we have crushed the Saxon and freed Ireland, what will we do? Oh, then you can go back to your slums, same as before. Whoop it up for liberty!

After Ireland is free, says the patriot who won’t touch Socialism, we will protect all classes, and if you won’t pay your rent you will be evicted same as now. But the evicting party, under command of the sheriff, will wear green uniforms and the Harp without the Crown, and the warrant turning you out on the roadside will be stamped with the arms of the Irish Republic. Now, isn’t that worth fighting for?

Alexis Guilbride is a research assistant in the Irish Labour History Museum, Dublin.

Further reading:

J.G. Douglas, Memoirs of Senator J.G. Douglas 1887-1954 (Dublin 1998).

E. O’Connor, Syndicalism in Ireland 1917-1923 (Cork 1988).