1916 in the de Valera papers

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 2 (Mar/Apr 2006), Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 14

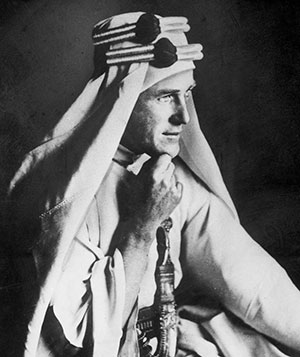

Eamon de Valera under guard after the Rising.

The de Valera papers, and a significant collection of those of his private secretary, Kathleen O’Connell, fit seamlessly into an existing collections profile within the UCD Archives that includes the papers of Frank Aiken, Seán MacEntee, Dr James Ryan and Seán and Maurice Moynihan, the last two serving at various times as private secretaries to de Valera and subsequently as secretaries to governments led by him. This body of private papers was augmented by the subsequent transfer by the Fianna Fáil Party of its own archives, establishing within a single custody an unprecedented nexus of interrelated collections. The de Valera papers are arguably the most significant of these collections. While not extending to the size of the Frank Aiken papers, they cover all aspects of an incomparably long career to a reasonably consistent depth.

1916 papers

The 1916 papers within the collection, while not constituting an overly impressive body of documents—extending to just four boxes out of a collection of 150 of textual material and 20 of photographs—are fairly representative of the collection as a whole and do contain interesting, and at times intriguing, material. Private paper collections may occasionally have a faintly manufactured feel to them, reflecting a habit on the part of the originator to add to original contemporary documents at a later time with ancillary matter such as reminiscence and reference material. The de Valera papers are no exception to this. De Valera had a habit of compiling dossiers on people and subjects central to his life and career. The 1916 documents include substantial files on the signatories to the proclamation and other leaders such as Thomas Ashe and Major John McBride. Most of these files contain some contemporary papers and an amount of later reference material, often including correspondence with de Valera concerning the individual or comment by him on relevant published work.

The papers relating to the activities of the 3rd battalion Dublin Brigade, including de Valera himself, have a similar complexion and are a mixture of some original papers and much later additional material. The file relating to the surrender of the Boland’s Mill garrison and the fighting in the Mount Street Bridge area, for example, includes:

• copies of Pearse’s order to surrender, the originals having been presented by de Valera to the National Museum;

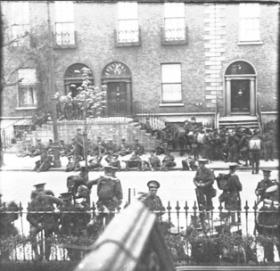

• original photographs of British soldiers in the Northumberland Road and Haddington Road areas, of de Valera’s surrender, and of the battalion marching in formation after the surrender;

• correspondence and photo-graphs concerning the presentation to de Valera by Neville Chamberlain in 1938 of the field glasses in de Valera’s possession at the time of the surrender of Boland’s Mills, and correspondence between de Valera and Capt. E. J. Hitzen, the British officer who accepted the surrender;

• memoir by Simon Donnelly, officer commanding C company, on the fighting in Mount Street, including correspondence with de Valera.

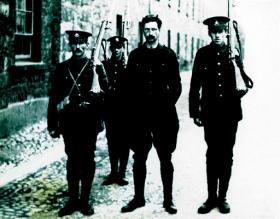

3rd Battalion of the Irish Volunteers under escort after their surrender. De Valera is marked by an ‘X’. (UCD Archives)

British documents

If there is material of conspicuous value within the 1916 papers, it is a file whose provenance is complex and obscure and whose contents document the British response to the Rising from the outbreak of hostilities until November 1917. It would appear to be an organic original file, but beyond a much later note written on an anonymous file cover there is no indication as to its origin. The file is labelled ‘Important British Documents & Letters, 1916 (Given to President de Valera)’. With the exception of a photographic copy of General Sir John Maxwell’s warrant of appointment as commander-in-chief of the British army in Ireland on 28 April 1916, the remainder of the file, amounting to over 130 documents, is original.

The file begins with a number of military intelligence reports pre-dating the Rising, the most extensive an eight-page report on the state of the country from Major Ivor Price to Lt Col. V. G. W. Kell at the War Office, which seems to be a copy of the report sent by Price to Major-General Friend on the same day and reproduced in B. Mac Giolla Choille’s Intelligence notes 1913–16 preserved in the State Paper Office (Dublin, 1966). This is an exception in that the overwhelming majority of the contents of the file would not appear to have been previously available.

French and Maxwell

The rather extraordinary nature of this material in this location could not be underlined more dramatically than by the presence of a seven-page holograph letter from Field Marshal Viscount French, commander-in-chief, home forces, to General Maxwell on 29 April, the day Maxwell was officially notified of his appointment as general officer commanding the forces in Ireland.

‘My Dear Maxwell.

Thank you for your letter which I have shown to the Prime Minister & am taking to the King.

We are sending you the Cavalry from Aldershot . . . I am glad to hear you have approved of all the steps which had been taken by Friend and Lowe before your arrival. You are in exciting and interesting surroundings.

I have had long talks with Carson and Redmond . . . Carson thinks the troops you have drawn into Dublin from Belfast should be sent north again as soon as you can spare them from Dublin. You must of course use your own judgement as to this but I only tell you what he says.

Cork has been represented to me by both Carson and Lord Midleton as a dangerous point—so I have sent you over there (to Queenstown) an infantry brigade of the 60 div. from Salisbury. A show of force will do good in the South.

Let me know your wants and they will receive prompt attention.

I don’t think there is much chance (now) of a German landing on the west coast of Ireland but that is what we must be prepared for.

Yours sincerely,

French

P.S. The King sent for me to London last night to report as to Ireland—His Majesty asked me to let you [know] (i) that in his view it was absolutely necessary to institute a search of all houses for arms as soon as this is possible. (ii) The King is very anxious that civilians, and those not engaged in rebellion should be cleared away & protected to the utmost. I told His Majesty that I would give you this message but assured him that you were fully alive to the importance of these points and would give them all the attention you could.’

British soldiers on Northumberland Road during the Rising. (UCD Archives)

Wimborne and Maxwell

On the same day, Maxwell received another handwritten communication from the lord lieutenant:

‘Dear Sir John Maxwell,

Thank you for your letter—I am glad that such good progress and effective action is reported.

I enclose a communiqué which in continuation of my previous action I propose with your concurrence to issue. I have several testimonies of the good effect they produce and respectfully suggest that they should be continued in my name as the best method of circulating credited information (which is I know eagerly looked for throughout the provinces) by means of the police, lord mayors and others and the wireless stations.

The lord chancellor has left a plan here of the Four Courts showing the position of all the most valuable historical and proprietary documents in Ireland and also, though less important, the exact position where the Great Seal was last deposited.

I hope that the situation will continue to improve and that you and your staff officer may be able to come to dinner at 8.30.

Yours sincerely,

Wimborne’

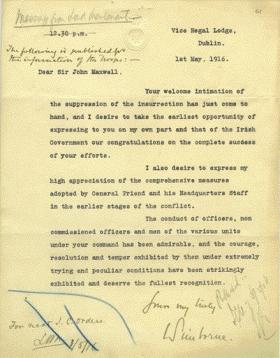

The contents of the file continue to surprise. Besides the official letter of congratulations on 1 May from Wimborne to Maxwell on the suppression of the Rising, which is ‘published for the information of the troops’, there is a personal handwritten note from the lord lieutenant:

‘Dear Sir John Maxwell

I add a private note of congratulations, and relief that it is over.

I note all the steps you are taking to restore normal conditions which seem to me if I may say so admirably conceived.

I appreciate and applaud your intention to recommend an alleviative expiation in active service in quiet districts.

I indicated this intention of yours to the prime minister last night and hope that it will not be opposed by the authorities.

When we are a little more settled down Her Excellency and myself hope to see you here and meet other members of your staff. I much regret to learn that in the midst of all these anxieties you have had serious domestic trouble.

I am

Yours sincerely

Wimborne’

Private letter of congratulations from Viceroy Wimborne to General Maxwell, 1 May 1916. (UCD Archives)

The executions

On 3 May French writes to Maxwell concerning the executions and Asquith’s surprise at the speed of events:

‘The prime minister expressed himself as “surprised” at the rapidity of the trial and executions—I pointed out that you were carrying out your instructions exactly & correctly and in strict accordance with military and martial law. He quite understands but asked me to warn you not to give the impression that all the Sinn Féiners would suffer death—I told him that the fact of 3 of them having been amended to much less severe sentences was evidence enough of the attitude you were adopting towards them and that I thought it much better to leave you alone to your own discretion. He agreed to this.’

On 6 May John Dillon writes to Maxwell concerning the adverse effects of the executions on public opinion after the ‘very severe shock’ created by the list in that evening’s paper:

‘The feeling is becoming widespread and intensely bitter—It really would be difficult to exaggerate the amount of mischief that these executions are doing.

As you kindly invite advice—there are two other matters I feel I ought to mention to you.

I do not believe it is a wise measure to arm special constables. They are not required and in the present temper in the city are very apt in my opinion to create disturbance.

I very much doubt the wisdom of instituting searching and arrests on a large scale in districts in which there has been no disturbance.’

British communications and intelligence reports

The remainder of the file includes further letters from both French and Wimborne to Maxwell, copies in his own hand of Maxwell’s communications with French, transcripts of deciphered messages from Asquith and Kitchener to Maxwell, as well as notes, memoranda and intelligence reports. The only indication within the file of any provenance is a ‘Headquarters, Irish Command’-registered file cover containing a two-page report on the present state of the Sinn Féin movement, 16 May 1916.

This is not the only instance of the presence of material in the de Valera papers causing surprise and fostering speculation. Recent work by Ronan Fanning on the Sinn Féin Funds case highlighted the presence of a corrected draft copy of Justice Kingsmill Moore’s judgement. How, when and why did the penultimate draft of a judgement of a High Court judge find its way into the private papers of a former and future taoiseach?

In the case of the de Valera 1916 file there is little internal evidence to track the papers to their present location. The common thread within the material is obviously General Sir John Maxwell, and it would appear safe to identify this as Maxwell’s personal unregistered working file for his period in Dublin. Its ultimate appearance as part of the de Valera papers may be unorthodox, and the route that took it there obscure and tantalising, but it is not entirely inappropriate that core research material for one of the most significant events of the twentieth century in Ireland should surface in the papers of the most significant Irish politician of that century.

De Valera returning to Dublin after his release from Pentonville prison, 1917. (UCD Archives)

Seamus Helferty is Principal Archivist in the University College Dublin School of History and Archives.

Enquiries: archives@ucd.ie, www.ucd.ie/archives or + 353 (0)1 7167555.