Zoology:Trevelyan’s rhinoceros and other gifts from India to Dublin Zoo

Published in

18th–19th - Century History,

Features,

Issue 4 (July/August 2010),

Volume 18

The mounted rhinoceros in the Zoological Museum, Trinity College Dublin—but is it Trevelyan’s? (Damien Maddox)

Sir Charles Trevelyan, notorious in Irish folk memory for the harsh way he coordinated famine relief in 1845–7, visited Dublin Zoo in the early 1860s, prior to his departure for Calcutta. He had been governor of Madras in 1859 but was recalled in 1860; in 1862 he was sent to India again, this time as finance minister. In 1863 he wrote to council members of the Zoological Society of Ireland, informing them that he had acquired a male rhinoceros on their behalf. He was keeping the young animal in Barrackpore menagerie, attached to the governor-general’s summer residence north of Calcutta. In mid-1864 it was shipped with a consignment of animals for London Zoo and arrived in Dublin in August. This was not the first rhinoceros to be seen in the zoo; in 1835 the society had rented a great Indian rhinoceros as well as an elephant for the summer months. By 1864 the zoo was in a fairly stable position, attracting up to 150,000 visitors a year. Trevelyan’s rhinoceros had cost £160, a considerable saving on the commercial price of at least £400. In recognition of his generosity Trevelyan was elected an honorary member of the Zoological Society.

Never settled

On 17 August the Irish Times described the new arrival as ‘perfectly quiet, and his eye, though small, is remarkably black, brilliant and intelligent’. But behind the scenes he was unsettled, becoming frantic on occasion and having what the staff described as epileptic fits. Revd Prof. Samuel Haughton, secretary of the society, a fellow of Trinity College and a physiologist, monitored the health of the animal with advice from fellow council members, including physicians Sir Dominic Corrigan and Dr C.P. Croker. They prescribed a diet of hay, cabbage, boiled rice with bran, milk and tonic powder. When the fits continued, they removed the cabbage and added potatoes.

The rhinoceros never settled in the zoo, becoming agitated on occasion and even breaking the bolt on his door. He must have been quiet at times because one boy got close enough to test the thickness of his skin with a pin and was promptly thrown out of the zoo. On the afternoon of 5 April 1865, however, the keepers urgently summoned council members Haughton, Dr Arthur Foot, Dr Benjamin McDowell and two veterinary surgeons: the rhinoceros was writhing in pain with a prolapsed rectum ‘to a frightful extent’ and was extremely distressed. They gave him a mixture of opium, castor oil, spirits of turpentine and aromatic spirits of ammonia, but to no avail. A telegram was sent to Abraham Bartlett, superintendent of London Zoo, asking for advice. Three hours later, his response arrived: ‘Send for a veterinary surgeon and let him treat the rhinoceros as he would a horse suffering from the same cause’. At 11.30 that night the council members went home, leaving the exhausted animal in the care of three experienced keepers. Trevelyan’s rhinoceros died at four in the morning.

Carcass acquired by Trinity College Zoological Museum

Field Marshal Frederick Sleigh Roberts (1832–1914) was president of the Royal Zoological Society of Ireland from 1898 to 1902 and encouraged officers serving with British colonial governments to acquire animals for Dublin Zoo. (Dublin Zoo)

As was the practice, the animal’s remains were auctioned. The Royal Dublin Society offered £15, planning to include it in their natural history collection; an offer of £16 was also made, but Samuel Haughton won with a bid of £17. Access to dead animals for dissection and study had been a significant motivator in the establishment of the zoo in the 1830s. The mortality rate was high and organisations interested in acquiring the carcasses included Trinity College, the Royal College of Surgeons, Dr Steevens’s Hospital and, later, the Catholic University of Ireland and the Royal College of Science of Ireland, as well as commercial organisations. Haughton had a particular interest in comparative anatomy; he also wanted the animal for the Trinity College Zoological Museum. He even bid against a colleague, Dr D.J. Cunningham of the Department of Anatomy in Trinity College, for a young orang-utan in 1885.

Trevelyan’s rhinoceros was transferred to the new dissecting room of Trinity College, where, 56 hours after its death, Haughton conducted the post-mortem. In his analysis published in the Dublin Quarterly Journal of Science, he commented that ‘the stench from the decomposing blood was almost intolerable, and several of my assistants were disabled by typhoid diarrhoea; this I escaped myself . . . and I was able to complete the entire muscular dissection in person, the results of which cannot fail to prove of interest to anatomists’. The cause of death was identified as ‘the improper administration of Indian corn, which fermented in the stomach and intestines’. Numerous tapeworms were also found and these, Haughton concluded, had caused the epileptic convulsions. The keeper who had disobeyed the strict diet for the rhinoceros by feeding it Indian corn had his wages reduced for a year.

More gifts from India

Another honorary member of the society based in India at the time was Lieutenant Colonel (later General) G.S. Montgomery, who sent Dublin Zoo a pair of Bengal tigers in 1861. That same year he wrote to the council describing his attempt to train a pair of nilgai to run with a tax cart; the nilgai, a large species of antelope found in India, went at such a ‘fearful pace’ that Montgomery did not try that experiment again. Over the following years he sent nilgai, panthers, bears, more tigers and other animals to Dublin Zoo.

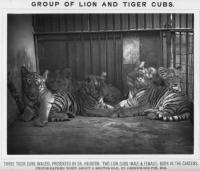

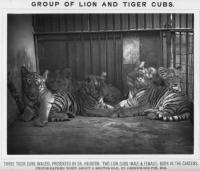

Three Indian tiger cubs (foreground), presented to Dublin Zoo in 1889 by Dr Heuston, sharing accommodation with two lion cubs. Heuston had cornered them in a cave after shooting their parents in a tiger hunt in India. (Dublin Zoo)

Below: Keepers sitting on a young Indian elephant in Dublin Zoo c. 1900. (Dublin Zoo)

When Richard Bourke, sixth earl of Mayo, departed for India in 1868 to take up the position of governor-general, he promised to acquire an elephant for Dublin Zoo. The following year he sent the zoo a six-year-old elephant called ‘Beharee Loll’ in India and renamed ‘Marksman’, but it died in transit. The earl, who was elected president of the society in December 1869, planned to replace the animal, but shortly afterwards Prince Alfred, duke of Edinburgh, gave Dublin Zoo a male elephant that he had acquired on a recent trip to India. Following the earl of Mayo’s assassination in 1872, his wife donated the animals that she had kept at Barrackpore menagerie. A male tiger in the collection had been brought from Burma in November 1868 and presented to Lady Mayo; the cub had been kept in Government House and had followed her around like a kitten until he became too big and was transferred to the safe confines of the menagerie.

More gifts from India followed. In 1889 Dr Heuston, a surgeon based in Bundelkhand, sent three tiger cubs to Dublin Zoo. He had cornered them in a cave after shooting their parents and, as reported in the society’s annual report for 1889, he had ‘entrusted them to his Kitmutgar [waiter] for conveyance to Bombay for shipment. The day following their start, the Kitmutgar returned, stating that the door of the cage having become unfastened, the tigers had managed to escape’. With the help of the police, Heuston recaptured the young animals and sent them to Ireland. He too was elected an honorary member of the society.

The appointment of Field Marshal Lord Roberts as president of the society in 1898 boosted the zoo’s connection with India. Roberts was commander-in-chief of the British army in Ireland at the time and had been commander-in-chief in India from 1885 to 1893. He circulated a list of desirable animals to army officers around the globe, asking for help for Dublin Zoo. Over the following years animals, including several species of monkey, tigers, leopards, wild sheep and parakeets, were sent to Dublin by officers serving in India, often at no cost to the zoo. Roberts took an active interest in the progress of donations. In 1899, after his son was killed in South Africa during the Boer War, he took up command in Africa. In June 1900 the council received a letter from him enquiring whether snow leopards being shipped to Dublin Zoo from Calcutta had arrived yet; in his letter Roberts mentioned that he was writing as he waited to receive an answer to his summons for the surrender of Johannesburg.

Keepers sitting on a young Indian elephant in Dublin.

During the twentieth century occasional gifts of animals arrived from India, including a young elephant that was presented to Dublin Zoo by the Indian government in 1971. Today the animals in Dublin Zoo are part of international conservation programmes and the traditional forms of acquisition no longer apply.

In 1865 Haughton had purchased Trevelyan’s young rhinoceros for the Zoological Museum in Trinity College Dublin. Recently a stuffed rhinoceros in the museum (opening picture) generated interest. Because of its small size there was speculation that it might be a rare Javan rhinoceros (also native to India). DNA tests identified it, however, as the more common great Indian rhinoceros. But Trevelyan’s, a male, was only two, or at most three, years old and therefore not yet fully grown. Nevertheless, conclusive evidence as to whether or not this is indeed Trevelyan’s rhinoceros remains elusive. HI

Catherine de Courcy is a writer and historian.

Further reading

C. de Courcy, Dublin Zoo: an illustrated history (Cork, 2009).