William Morris & Irish politics

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 1 (Spring 2000), Volume 8

The Hammersmith branch of the Socialist League (founded by Morris in December 1884)-Morris is fourth from the right, middle row. (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

The reappraisals that occurred during the centenary of the death of William Morris (1834-96) further confirmed him as one of the outstanding figures of nineteenth-century Britain. A multi-talented individual he achieved prominence in the arts as a poet, novelist, designer, printer, stained-glass artist, weaver, dyer and, to a rather lesser degree, as a painter. He was also a crusading conservationist and a pioneering environmentalist. In politics he stands out as perhaps the most original contributor to late nineteenth-century British socialism. His vitality as a writer, and his energy as an agitator, served him well in this sphere.

Throughout his political life Morris was a keen observer of events in Ireland. It was a country that he had first visited while on business in October 1877, before his conversion to socialism, and he had found evidence of what he saw as exceptional poverty. ‘The villages we passed’, he wrote to Georgiana Burne-Jones, ‘were very poor-looking, and the cottiers’ houses in outside appearance the very poorest habitations I have yet seen, Iceland by no means excepted.’ Although he found the country ‘much more beautiful’ than he had expected, Dublin was dismissed as a ‘dirty and slatternly’ city and the Guinness brewery seemed to Morris to be ‘the only thing of importance there’. Moreover, Morris’s innate aversion to injustice was roused by stories he heard in Tullamore of the savagery of government yeomanry during the 1798 rebellion, and he referred wryly to passing the Curragh in County Kildare where ‘our army of occupation sits’.

‘Damn Tweedle-dum and blast Tweedle-dee’

Morris was in his late forties when he began to take a serious interest in politics. His initial involvement was with Radicalism and he supported the Liberals against the Conservative party during the general election of April 1880. The Irish Land League, which had been founded the previous October, played a role in the defeat of the Conservatives and many in the British Radical movement, including Morris, expected the new government to be more accommodating to Irish demands. The Liberals did introduce a land bill that went some way towards placating the Irish tenant-farmers but they also, to the chagrin of the advanced Radicals, brought forward a most astringent coercion bill that allowed for the internment without trial of Land League activists.

Morris was quickly disillusioned by the Liberal-Radical alliance and he later wrote that the lack of progressive action by the new administration, ‘especially the coercion bill and the stock jobber’s Egyptian war’, drove him away from Radicalism in the direction of the newly-emerging socialist movement. He concluded that the ‘age of shoddy’ was doomed to collapse, and with regard to the Liberal and Conservative parties it was a case of ‘damn Tweedle-dum and blast Tweedle-dee’.

The Democratic Federation, which emerged partly as a result of opposition to coercion in Ireland, attracted Morris’s attention and he joined this socialist organisation in January 1883 and became one of its most prominent members. His conversion surprised many and the Donegal poet William Allingham noted in his diary that Alfred Tennyson was ‘shocked’ by the news. Nonetheless, Morris was to remain a staunch advocate of socialism until his death thirteen years later, and he was one of those who successfully proposed renaming the organisation the Social Democratic Federation (SDF).

Supporting Home Rule

The SDF was aggressively in favour of Irish home rule and took a leading role in the anti-coercion movement. Ernest Belfort Bax, a leading member, later remarked that the organisation was ‘largely occupied’ with Ireland during its formative years. Morris, similarly, strongly supported home rule for Ireland and while lecturing for the SDF came into contact with many members of the Irish community in Britain. In early May 1883, for instance, he lectured at the Irish National League rooms on Blackfriars Road in London: ‘Parnellites to the backbone; but dear me! such quiet respectable people!’ He assured them of his sympathy for their views and professed admiration for ‘their ancient literature’. One of the principal organisers of this meeting was Peter O’Leary, an important supporter of the Irish rural labourers’ movement although not a socialist.

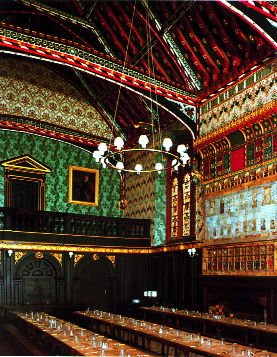

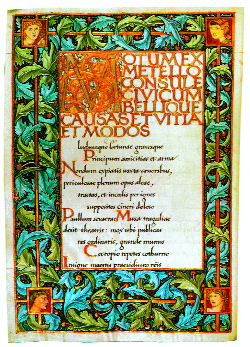

Examples of Morris’s work as an artist and designer-(left) interior of Queens’ College Hall, Cambridge, 1866-7-(right) manuscript of Horace’s Odes, 1874. (Woodmansterne and Bodleian Library, Oxford)

Portrait by G.F. Watts.

In fact, while supporting the Irish demands, Morris remained wary of the social conservatism of Irish nationalism. ‘We are internationalists not nationalists’, he wrote to a correspondent, ‘yet we sympathise with the Irish revolt against English tyranny.’ He brought this perspective with him when he left the SDF to help form the more left-wing Socialist League in December 1884. The League’s position on imperialism was outlined in the first issue of the group’s newspaper, The Commonweal:

The establishment of socialism…on any national or race basis is out of the question…No, the foreign policy of the great internationalist socialist party must be to break up these hideous race monopolies called empires, beginning in each case at home. Hence everything which makes for the disintegration of the empire to which he belongs must be welcomed by the socialist as an ally.

In January 1888 Morris was to write that the Irish question ‘will educate many [in Britain] in revolution’, and in this view he closely followed Karl Marx who had argued the same perspective during the 1870s.

Two of those who signed the Socialist League’s founding manifesto were of Irish extraction and one, John Lincoln Mahon (formerly ‘MacMahon’), became the organisation’s first secretary. By 1885 British socialists, and the SDF in particular, had pulled back somewhat from Irish support work and focused instead on social agitation and recruitment in Britain. The SDF ultimately decided, as it explained in January 1887, that the best assistance it could give ‘to the Irish in their struggles is to occupy as much as possible the government with an agitation on behalf of the workers of Great Britain’. The Socialist League rejected this rather circuitous form of solidarity and took a stronger line on the Irish question. Moreover, Mahon made serious efforts to recruit members in Ireland itself.

The limitations of Parnellism

The issue of Irish home rule rose high on the British political agenda in 1885 when, with a general election pending, overtures were made to Charles Stewart Parnell to secure the Irish vote. The return of 335 Liberals, 249 Conservatives, and eighty-six Home Rulers meant that the Irish were placed in a strong position in the new parliament. When Liberal leader Gladstone converted to home rule, Parnell threw his support behind the Liberal party and work began on a bill to satisfy Irish aspirations.

William Morris, as editor of The Commonweal, showed a marked interest in these developments. In October he wrote that Parnell, in all probability, would succeed in his objective and he mused that the next parliament could be the last in which Irish representatives sat. Morris rejoiced at the damage that this would inflict on the British Empire, but he also sounded a note of warning for those who would exaggerate the progressive nature of the Irish home rule movement. ‘Will socialists’, he asked, ‘find their work any easier in the Parnellite Ireland than now? Will Michael Davitt be as dangerous a rebel as he is now?’

For Morris the answer to both these questions was obvious. The Parnellites, in his opinion, wanted ‘pretty much the state of things which Liberal reformers want to realise in England as a bar to the march of socialism’. While Morris was being rather far-fetched in his estimation of Parnellite and Liberal jitters regarding socialism, he was correct in perceiving limitations to the nationalist project. Radicalism on constitutional issues did not necessarily imply radicalism on social issues. On the land question he argued that the Irish objective of peasant-proprietorship meant

an improved landlordism founded on a wider basis and therefore consolidated; that would lead, it seems to me, to founding a nation fanatically attached to the rights of private property (so-called), narrow-minded, retrogressive, contentious and—unhappy.

Morris supported home rule but he held no illusions about the type of society that would emerge. Pointing to the example of Italy he contended that despite national freedom poverty remained because the class system still stood. A solution to Ireland’s social problems, he insisted, could only be found through international revolution. If only the Irish could ‘make up their minds that, even if they have to wait for it, their revolution shall be part of the great international movement; they will then be rid of all the foreigners that they want to be rid of’. This was a position that appealed to few in late nineteenth-century Ireland.

The Dublin University Review and Morris

Among those who evinced some interest in the ideas of William Morris was Thomas William Rolleston, then editor of the Dublin University Review, who wrote to the London office of the Socialist League in July 1885 requesting for review ‘all the numbers of The Commonweal containing press by Mr W. Morris’. The proprietor of this literary and cultural journal, the Protestant nationalist Charles Hubert Oldham, similarly displayed some interest and, on the recommendation of Michael Davitt, he took out a twelve month subscription to The Commonweal in August. Rolleston subscribed to the paper in January 1886.

Rolleston, a member of the Young Ireland Society, did not convert to socialism but he did maintain an interest that saw articles on the subject published through 1885 and 1886. In August 1885 the Dublin University Review carried a lengthy survey, probably written by Rolleston himself, of the material that had been requested from London. Titled ‘The Socialist League and its Poet’ the article reflected Rolleston’s aversion to industrialised society and suggested that if Ireland went down this route ‘so surely will the doctrines of the Socialist League take root in our soil, and in due time bear, in our streets also, that crop of dragon’s teeth’. Rolleston predicted that just as the nineteenth century had been ushered in by revolution ‘in which the system of government by caste was eradicated by fire and sword’ so too would it be ushered out by another revolution ‘aiming at even more radical changes in the face of European society’.

Rolleston concurred with Morris that capitalist society was ‘monstrous and horrible’ and detrimental to ‘high or beautiful human qualities’.

Dublin’s nationalist Weekly Freeman depicts Gladstone championing Home Rule-his 1886 bill was described by Morris as ‘a piece of constitution-making of the most ingenious kind’.

In fact, Morris’s position was that the destruction of capitalism was necessary for art to flourish. Rolleston recognised this and commented that it seemed as if Morris’s ‘artistic sense…has had at least as powerful an effect as his humanity or his reason in inducing him to throw himself into the socialist movement of today’. In general, the article provided quite a sympathetic introduction to Morris’s politics for Dublin intellectuals.

Morris visits Dublin

A branch of the Socialist League was established in Dublin in late 1885. Its members were primarily working class and of limited means (although one leading figure, Kilkenny-born John O’Gorman, was an accountant). Nonetheless, a number of modestly successful public meetings were organised and the branch received some coverage in the national press. In order to boost its profile a member of the branch, the Danish lithographic artist Fritz Schumann, was delegated in early 1886 to invite a leading British socialist to address a public meeting in the city. Edward Aveling was approached but proved unavailable and the prospects of attracting a speaker seemed bleak. Then, fortuitously, a group of Dublin intellectuals associated with both the Contemporary Club and the Saturday Club asked Morris to lecture in Dublin on the aims of art and offered to pay his expenses should he agree to travel. A member of the Dublin Socialist League, the Russian R.I. Lipmann, was connected with this group whose prime mover was the printer James Walker. C.H. Oldham and T.W. Rolleston were more than likely also involved in this venture. Morris, who was indefatigable as a lecturer, quickly agreed to the proposal and he also made plans to lecture for the Socialist League branch while in Dublin.

Morris set out for Dublin on Thursday 8 April and, having first had his spectacles blown off by a cold wind, he surveyed the Wicklow mountains and the Irish coast from the deck of the ship at 5.30am the following morning. He landed at Kingstown some ninety minutes later where he was met on the quay-side by six or seven members of the local branch. It was a time of great political excitement in Ireland as Gladstone’s home rule bill had been introduced in the House of Commons the previous day. In a letter home on the day of his arrival Morris reported that ‘the news was there before us, Gladstone’s speech all in full in the Irish papers. It was’, he remarked cynically, ‘as I supposed it would be—a piece of constitution-making of the most ingenious kind.’

Later that evening Morris gave a lecture on the ‘Aims of Art’ at the Molesworth Hall for the people who had initiated his visit. The attendance, he reported, was made up primarily of ‘ladies and gentlemen’ with ‘a few workmen scattered among the audience’ and some of the Dublin socialists put in an appearance. In his lecture he argued strongly for socialism ‘as a necessity for the new birth of art’. Many of the ‘respectables’ walked out of the hall at an early stage clearly displeased by the content of Morris’s speech.

The following evening, on 10 April, he gave another lecture; this time for the Saturday Club under the title ‘What is Socialism?’. The Saturday Club, which had been founded in 1885, provided an independent debating forum every Saturday evening in the Rotunda for radical workingmen. The Dublin socialists were very much involved as were both James Walker and the barrister John F. Taylor of the Contemporary Club. Morris’s meeting attracted an audience of over six hundred to the Round Room of the Rotunda. The crowd was still palpably excited by the news of the home rule bill and nationalist fervour rippled through the evening. At one point Morris was forced by uproar to apologise ‘with all good will’ for referring to the main street as Sackville Street which the nationalists wanted renamed as O’Connell Street. In general, however, his speech was well received. He argued that trade unionism had achieved all that it was likely to achieve for the working class and it was now time to move beyond labourism. Workers, he said, should declare: ‘We will have masters no longer, because we don’t need them. What we claim is that men shall have all the produce of their labour’. A poor debate followed but when the chairman attempted to wind up the evening he was severely heckled and the excited crowd broke into a fifteen minute rendition of ‘God save Ireland’. Morris, nonetheless, left feeling that the audience had been generally sympathetic.

Over the following days Morris met with the members of the Socialist League branch and he spoke under their auspices at a public meeting in 30 Great Brunswick Street on Tuesday 13 April. During his free time he took a trip to the Wicklow mountains which he found ‘very beautiful’. He also renewed his acquaintance with Dublin city and he discovered that he rather liked its shabby air. The Contemporary Club, situated near Trinity College, was on his itinerary and during his visit there he met a number of Dublin’s leading intellectuals and writers including W.B. Yeats. Certainly, he was made aware of the strength of feeling on the issue of home rule and, on his return to England, he informed his wife that:

On whatever other points the Irish are wild, they are quite cool, sensible, and determined on the Home Rule question. I met some agreeable middle-classers there and had much talk—far too much in fact; I doubt if there is an iron pot in Dublin with a leg on it by this time.

Conclusion

Writing in The Commonweal, shortly after his return to Britain, Morris reflected on his Irish visit. While admitting that a short stay in Dublin (‘one place in the country’) could not give him a comprehensive view of Ireland he did reach some conclusions. First, he believed that religion provided the primary impediment to socialism although he hoped that when home rule was established ‘the Catholic clergy will begin to set after their kind, and try after more and more power, till the Irish gorge rises and rejects them’. The Protestant religion in Ireland, he concluded, was more ‘dogmatic, and not political…[and thus] hopeless to deal with’. Morris may have been influenced on the question of religion by members of the Dublin Socialist League, many of whom took a similar position to that outlined in his article.

He also decided that his estimation of Irish nationalism had been largely correct and he realised, perhaps more than before, that the struggle for home rule, while damaging the British Empire, did little to help the emergence of socialism in Ireland. In what was to remain his analysis of Ireland, Morris wrote:

It is a matter of course that until the Irish get Home Rule they will listen to nothing else, and equally so that as soon as they get Home Rule they must deal at once with the land question. On the whole, I fear it seems likely that they will have to go through the dismal road of peasant-proprietorship before they get to anything like Socialism; and that road in a country so isolated and so peculiar as Ireland may be a long one.

Fintan Lane is a temporary lecturer with the Department of Government and Society at the University of Limerick.

Further reading:

F. Lane, The Origins of Modern Irish Socialism, 1881-1896 (Cork 1997).

F. MacCarthy, William Morris: A Life for Our Time (London 1994).