Three Oxford liberals and the Plan of Campaign in Donegal, 1889

Published in

18th–19th - Century History,

Features,

Issue 3 (May/June 2011),

Parnell & his Party,

Volume 19

‘The Fight For Bare Life On The Olphert Estate’ (United Ireland, 12 January 1889, J.D. Reigh). Paddy O’Donnell and his family peacefully remove rocks from a potato bed outside their cabin (top left); the tenant’s family and friends barricade the house (top right); the evicted family pose outside their roofless house ‘after the battle’ (bottom right); the emergency men and a constable flee from a volley of stones ‘in the thick of the fight’ (bottom left); and in the main picture Father McFadden shouts at Major Mends, the police commander, who has just ordered his men to shoot: ‘For God’s sake spare my poor people’. Behind him Canon Stephens urges O’Donnell’s garrison to surrender. (National Library of Ireland)

Following the defeat of Gladstone’s first Home Rule bill in June 1886, some of Charles Stewart Parnell’s lieutenants decided to raise morale and lower rents by renewing the land war that had caused so much havoc and fear since the founding of the Irish National Land League in October 1879. Although Parnell opposed this new agitation, in October 1886 Timothy Harrington, John Dillon and William O’Brien launched the ‘Plan of Campaign’ that called for withholding rent on estates whose owners refused to reduce them by 20–40%. Tenants who joined the Plan would hand over their rent, less the reduction, to a trustee—often the parish priest—who held it in escrow until the landlord surrendered to their demands.

The Olphert evictions

Of the roughly 200 estates affected by the Plan only a few lay in Donegal. One belonged to Wybrants Olphert, whose 18,133 acres, valued

at only £1,802, surrounded Falcarragh and Ardsmore, north of Gweedore. Descended from a Dutch Protestant who had bought the property in 1661, Olphert was the longest-serving magistrate in the country. Tenant unrest had been minimal up to 1885, when another economic downturn produced arrears of £1,200, and the owner’s creditors pressed him to evict the delinquent tenants.After negotiations collapsed, most of the Catholic tenants adopted the Plan in January 1888. The obdurate Olphert resolved to fight this tenant ‘conspiracy’ despite two formidable adversaries—Father James McFadden, the parish priest of Gweedore, who was both loved and feared by his parishioners, and his curate, Canon Daniel Stephens. Both clergymen led the demand for a 20% abatement of judicial rents and 40% on non-judicial rents. Seeking to squeeze some rent out of the rebellious tenants, the agent Hewson obtained scores of ejectment decrees. When this threat failed to produce any rent, the purge of Plan tenants began in January 1889. To save Olphert from surrender, the implacable Irish chief secretary, Arthur Balfour, organised a secret syndicate of English and Irish magnates that assumed control and ran the evicted farms like cattle ranches. Dublin Castle also helped by prosecuting Father McFadden for promoting the Plan. Sentenced to three months in jail, McFadden lodged an appeal that prompted the judge to double the length of his confinement. Canon Stephens was soon arrested on the same charge, convicted and imprisoned for three months. The evictions and prosecutions resulted in a stifling boycott of the Olphert family, who were denied fuel and basic services. Camping out on Ballyconnell demesne, dozens of police patrolled the grounds night and day.

The Olphert evictions drew reporters and artists from afar. Among the latter was United Ireland’s clever comic artist John D. Reigh, whose ‘The Fight For Bare Life On The Olphert Estate’ (p. 34) highlighted some dramatic incidents in the struggle around Falcarragh. In an even more damning cartoon, Reigh’s opposite number at the Weekly Freeman, John Fergus O’Hea, used the Unionist government’s by-election defeat at Rochester to underscore the horrors of the Olphert evictions. In ‘A Set Off Against Rochester’ (above) a sadistic policeman and bailiff (or ‘emergency man’) storm out of an evicted cottage holding in triumph the defenders—two doll-like infants.

|

| ‘A Set Off Against Rochester’ (Weekly Freeman, 27 April 1889, J. F. O’Hea). Here two prime agents of eviction—a policeman and a bailiff—emerge from a besieged cabin at Falcarragh holding in triumph the two defenders. As the caption reveals, ‘Balfour’s Braves’ have just captured the garrison, consisting of two babies aged six and eight months. (National Library of Ireland) |

Three Oxonians

Among the prominent visitors to Falcarragh at this time were Ulster’s tenant-rights activist T.W. Russell MP, the American journalist W.H. Hurlbert, delegates from the Manchester Liberal Association, Maud Gonne and her cousin May, and three Oxonians. The leader of the Oxford trio was the maverick radical MP for Camborne in Cornwall, C.A.V. Conybeare (1853–1919), who had spent three years at Christ Church before becoming a barrister. This ardent Home Ruler and unrelenting critic of Balfourian coercion was determined to publicise Irish evictions. In the course of an interview Olphert complained bitterly that he was ‘the worst treated landlord in Ireland’ despite his long residence and vowed to evict every Plan supporter if they rejected his counter-offer. Along with two Parnellite MPs, Conybeare was denied permission to inspect the battering ram, known derisively as ‘Balfour’s Maiden’, which the police had procured from a Derry firm to deal with barricaded dwellings. Wherever they went these interlopers were followed or ‘shadowed’ by constables.

One of the other Oxonians who arrived in the second week of April was Godfrey R. Benson, a young lecturer in philosophy at Balliol College. Born near Alresford, Hampshire, in 1864 and educated at Winchester, he took a first class degree in classics and became a college lecturer. If Benson never took tutorials with Professor Thomas Hill Green, the beloved godfather of the new liberalism, who died much too young in 1882, he must have been imbued with the principles of ‘political obligation’ and collectivism that inspired so many Balliol men.

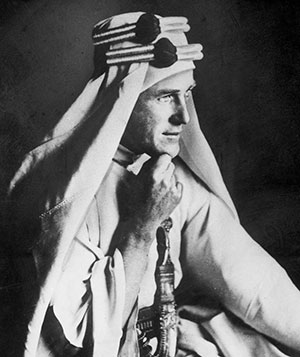

The third Oxonian, Henry Harrison, came from a northern Irish family that boasted a judge. Born in Holywood, Co. Down, in 1867, he moved with his mother, a keen Home Ruler, to Mayfair after the death of his father in 1873. A talented athlete, he captained the cricket and football teams at Westminster School and matriculated at Balliol in 1887, where he excelled at sports and honed his liberal instincts. Tutored by R.L. Nettleship, the devoted disciple and memoirist of Green, he became secretary of the Oxford Home Rule Club. During the spring ‘vac’ of 1889 he and Benson decided to embark on a walking and reading tour of Donegal. Upon reaching Gweedore, the teacher and his student heard about the Olphert evictions and headed for Falcarragh in search of both excitement and a just cause.

|

| ‘Triumph of Law and Order in Gweedore’ (United Ireland, 27 April 1889, J.D. Reigh). In the main picture a police sergeant has collared Harrison in his Ulster overcoat while handing a loaf of bread to a mother with her infant. Opposite Harrison’s cameo portrait (top left), a woman with two babies has been arrested during ‘A Midnight Police Raid’ (top right). |

Evicted tenants urged to reoccupy

During their walkabout they urged the evicted tenants to reoccupy their homes. Some 50 families took their advice and re-entered their cabins illegally before dawn on 15 April. Some said that they would rather risk prison than sleep rough or go to the workhouse. Once inside, they barricaded the doors and windows to prevent the police from entering. An infuriated Olphert demanded that the sheriff’s party return and expel these trespassers. But instead of evicting them again the police posted guards at each abode and threatened to arrest anyone who stepped outside.

To relieve the hunger of the tenants trapped inside, the three English Samaritans bought bread, teacakes, tea and sugar, and wrapped these provisions in small parcels that could be slipped inside the door. To bypass barricaded doors, Harrison tied the bundles to a string and lowered them down the chimney. He also threw a few of them through holes in the roof. When one of their police ‘shadows’ asked what they were doing, Benson coolly replied that they were feeding cats.

Shortly before midnight on 16 April Harrison approached Manus McGinley’s house and asked the occupants in Irish to open the blocked door. Eventually he lifted the door off its hinges and handed over some food, at which point Head Constable Mahony ordered him to cease and desist. Harrison ignored him and, after a minor scuffle, Mahony handcuffed Harrison and hauled him off to the barracks, where he was denied visitors. When Conybeare and Benson offered to share their friend’s fate, Mahony refused to oblige on the grounds that the Cornish MP was a man of ‘social substance’. Charged with ‘giving succour’ to the reoccupiers, Harrison spurned bail and spent two nights in police custody before being conveyed to Derry jail. In the meantime his companions carried on their relief efforts around Drumnatinney.

Reigh’s vivid cartoon, ‘Triumph of Law and Order in Gweedore’ (above), depicts Harrison being arrested while handing a loaf of bread to a mother with her infant. On the morning of Harrison’s transfer to Derry jail some 200 boisterous supporters jeered the police. When the horse pulling the cart with Harrison on board shied and refused to budge, the crowd burst into guffaws of laughter. Angry and embarrassed, the head constable sent for another conveyance and ordered his men to ‘get your batons and knock the devil out of them’. Among those beaten or shoved by the police were several Parnellite MPs and priests, along with Conybeare and a Daily News reporter. For this compelling reason the Freeman’s Journal accused the police of acting with ‘relentless savagery’. While delivering more food to the ‘starving’ tenants, Conybeare suddenly wheeled around and called his police escort ‘Balfour’s booby’.

|

| ‘What Our English Visitors Saw’ (Weekly Freeman, 21 September 1889, J.F. O’Hea). Pointing to a row of demolished cottages, the local guide tells a group of English liberal visitors that the government ‘sent down the sojers and polis with battering-rams and petroleum—and look at the place now. Shure there isn’t a house standin’ for miles about except the polis-barracks up there.’ (National Library of Ireland) |

‘If I had my clothes on I’d arrest you’

All this defiance moved the authorities to launch a surprise attack on the reoccupied houses before dawn on 18 April. Wielding sledgehammers and hatchets, the police and bailiffs broke down scores of doors and arrested the occupants. Among those driven out was the crippled Widow Coyle, a 90-year-old man and a woman with twin babies. Awakened by news of this nocturnal assault, Conybeare rushed to the lodging house of deputy divisional magistrate David Cameron, brushed aside the landlady and burst into the bedroom. Denouncing the evictions and this midnight assault, he demanded that Harrison be treated like an ‘English gentleman’ and granted bail or a solicitor. Equally enraged, Cameron jumped out of bed shouting: ‘Get out or I’ll arrest you. By God, if I had my clothes on I’d arrest you.’ A slightly calmer Conybeare then thanked Cameron for his ‘gentlemanly and magisterial demeanour’ and withdrew. Once outside he led his police ‘shadow’ on an exhausting foot race around the village.

On 22 April, Harrison and eight of the tenant resisters left Derry for their trial in Falcarragh. Deferring no doubt to his élite status, the magistrates released the undergraduate without bail. Indicted for promoting the Plan, Conybeare used his legal skills to defend himself, while Edmund Leamy MP handled Harrison’s defence. For some reason ‘Professor’ Benson was not prosecuted, despite being named a co-conspirator. He did, however, follow the advice of friends and left for Oxford in order to avoid arrest.

The trial of Harrison and Conybeare dragged on for six days, with prolonged interrogation of police witnesses and some caustic cross-examining by Conybeare. While Harrison and his fellow defendants were acquitted, Conybeare was not so fortunate. Convicted of promoting the Plan, he was

sentenced to three months in prison with hard labour. When the police escorted him out of Falcarragh, he urged his supporters to cheer for the Plan. Later his complaints about the appalling conditions in Derry jail provoked the Irish permanent undersecretary, Sir Joseph West Ridgeway, into calling him a ‘mean, dirty, little cur’. Leamy denounced the trial as a ‘miserable parody of Continental tyranny’. On the other hand, the heroism of Conybeare and Harrison brought them invitations to address Home Rule rallies in England.

More evictions drew more English liberals, some of whom were allowed to inspect but not photograph the Falcarragh ram. Ejectments continued on and off through the autumn and then resumed in November 1890. In a public letter Olphert’s daughter denied the existence of any distress and accused the Plan leaders of having intimidated their formerly loyal tenants. The duke of Abercorn, chairman of the Donegal Central Committee of the Olphert Defence Fund, urged Ulster loyalists to donate money to rescue the proprietor from ‘this monstrous and cruel conspiracy’. A cheque for £1,500 from English sympathisers eased Olphert’s financial woes, but it did nothing to end the dispute. By December 1890 over 350 families or almost 2,500 individuals had been driven out, and only 10% of them were readmitted. In O’Hea’s cartoon, ‘What Our English Visitors Saw’ (below), a local guide informs some well-meaning English liberals of how government forces purged the district of every inhabitant and wrecked their homes. Not until the early 1900s did the evicted families return to their homes. HI

L. Perry Curtis Jr is Professor Emeritus of History and Modern Culture and Media, Brown University, Rhode Island.

Further reading:

L.M. Geary, The Plan of Campaign, 1886–1891 (Cork, 1986).

H. Harrison, Parnell vindicated: the lifting of the veil (London, 1931).

F.S.L. Lyons, John Dillon: a biography (London, 1968).

M. Richter, The politics of conscience: T. H. Green and his age (Cambridge, MA, 1964).