The New York draft riots of 1863: an Irish civil war?

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 2 (Summer 2003), Volume 11The New York draft riots of 1863, which feature in the violent finale of Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York, were the worst in American history, causing over 100 deaths and 1.5 millio

The burning Ninth Congressional District draft office, where the riots started on the morning of Monday 13 July, as depicted in Martin Scorsese’s ‘Gangs of New York’. (Warner Brothers)

n dollars’ worth of damage, about 150 million dollars in today’s money. Starting on Monday 13 July 1863 as a protest against the implementation of the Union’s Conscription Act, the demonstrations escalated into a widespread insurrection against federal authority. The Conscription Act answered the desperate need to find men to fight the Civil War. It called for the drafting of 200,000 men but allowed for commutation on payment of $300, a clause that was widely believed to favour the rich. Opposition politicians throughout the North called the act unconstitutional, and planned protests against its implementation.

In the execution of the law, New York was a critical focal point. In 1863 the city had a population of about 800,000—a spectacular rise from the 50,000 inhabitants of 1800. Most of the increase came from immigration, from within the US and from overseas. The majority of the foreign immigrants were Irish, crowding into the slums of the Lower East Side and the working-class areas of the Upper East and West Sides. In 1863 New York extended to just north of present-day Central Park, which was then under construction. Since 1811 the city had adopted the rectangular pattern of streets running east–west and avenues north–south. It was crowded and dense and suffered from serious air pollution, bad sanitation, numerous tenement firetraps, and endemic corruption.

Gotham city and the draft

When the draft law came into force, the lower classes of New York were almost totally alienated from federal and city power structures. The city’s ‘natural’ party of government, the Democratic Party, was split between the War Democrats who supported the Lincoln government and the Peace Democrats who sought a negotiated peace with the Confederacy. Peace Democrat politicians, who were the loudest in assuring the people that the draft was immoral and unconstitutional, were also powerless to stop it. Both the mayor’s office and the presidency were in the hands of the Republicans, an alliance of anti-slavery activists, reformist Protestants and anti-immigrant nativists. No doubt the casualty lists after the great battles of that summer (Chancellorsville, Vicksburg, Gettysburg) served to increase the sense of threat and anger. Further, high wartime inflation depressed the purchasing power of wages and deprived the working classes of the benefits of the booming wartime economy.

Selection for the draft was random, with balloting by electoral district under the supervision of a provost marshal. Colonel Robert Nugent, born in County Down, was appointed to supervise the New York draft. Nugent had fought with the ‘Fighting Irish’ and was wounded at the battle of Fredericksburg (December 1862). His initial plan seemed sensible—to implement the draft in a rolling manner, starting in the Ninth Congressional District (Manhattan north of 40th Street) and then proceeding to the poorer areas. If trouble was to come, it was expected to occur downtown in the notorious slums of the Five Points and Corlears Hook.

The piecemeal implementation meant that all protest would focus at any one time on a single draft office only. The first day, Saturday 11 July, proceeded quietly. Sunday 12 July was a day of rest, but the fact that it was also the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne may have played on the minds of the Catholic Irish. A later generation would spend Sundays at ball games or at the seaside. In the sweltering July heat of that Sunday in 1863, most New Yorkers congregated in bars and on stoops to drink and talk politics. Through the saloons and tenements the word circulated: on Monday 13 July, factories, shipyards and docks would close; the day was to be one of protest against the draft.

The riots: day one

The protest began early. Many factory workers and labourers stayed away from their jobs. Where they did show up, groups of them demanded that the factories close for the day. As the hot morning of 13 July wore on, a large crowd began to assemble at the draft office of the Nineteenth Ward, Ninth District, where selection was to continue that morning. Lulled by Saturday’s success, Nugent and the police commissioner did not expect any trouble.

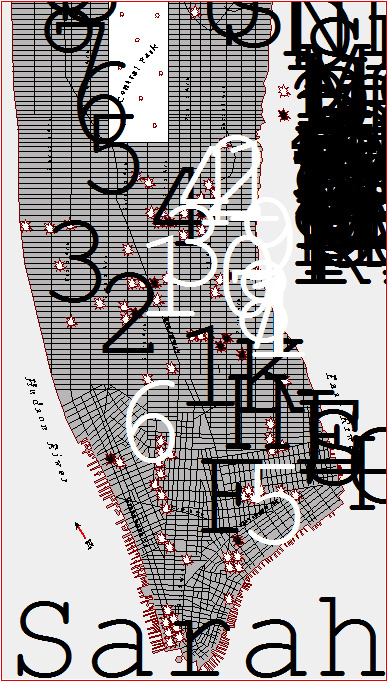

New York and the draft riots 1863.

Two leading members of Volunteer Engine Company Thirty-Three, known as the ‘Black Joke’ company, had already been selected in Saturday’s ballot. Volunteer fire companies were unique organisations—they were often composed of ‘sports’, young men who were also members of violent street gangs. The fire companies greatly resented not being exempted from the draft, as they were from militia service. Soon after selection of names began, the firemen stormed the draft office, burning all the draft papers they could find and sending the staff away in flight. Following this lead, the crowd set fire to the office and adjoining buildings. Some of the policemen were beaten and the rest fled.

The lynching of an African-American on Clarkson Street, Harper’s Weekly, 21 July 1863. (Museum of the City of New York)

The first policeman to approach the scene was Superintendent James Kennedy, in civilian clothes. He had heard rumours of trouble that morning and had come on a reconnaissance. Recognised by the crowd, now a mob, he was chased and beaten beyond recognition. Colonel Nugent, at the Park Barracks, heard of the trouble and sent a squad of 32 soldiers of the Invalids Corps, but they were also set upon by the mob and two were killed. This typified the early reaction of the authorities. Squads of police or militia were despatched in groups that were too small to have any effect against the angry mobs. Rioters burned buildings, looted shops, cut telegraph wires and tore up railway tracks. Groups ranging in size from 50 to several hundred began to search for more Republican victims.

Soon columns of smoke were rising through the city. An onlooker noted crowds of women as ‘ferocious’ as the male rioters, ‘swinging aprons and handkerchiefs, and cheering and urging them onward’. Diarist George Templeton Strong watched a mob looting and burning a house reputed to belong to Horace Greeley, abolitionist editor of the New York Tribune. ‘The beastly ruffians are masters of the situation and the city’, he wrote later in his diary. He was right. Most of the city and state militia were away in Pennsylvania backing up the army’s Gettysburg campaign, leaving some 1400 police on duty against thousands of rioters.

Even allowing for the fact that the police were deprived of army support, the authorities’ early response was generally ineffective. One reason was the divided command of the army and militia. Another was the sluggishness of the elderly generals who commanded these units. The one army general with the least formal authority, General Harvey Brown, commander of the regular army garrisons in the New York harbour forts, proved equal to the occasion. Brown made his way to police headquarters, where his presence stiffened the leaderless police. As the week wore on, he succeeded in getting more militia units made available for riot duty.

With Superintendent Kennedy hospitalised, police authority fell upon Thomas Acton, the civilian commissioner. Though badly rattled on the first day and possibly fortified by the presence of Brown, he remained at his post continually for the four days and provided the police with the essential leadership they needed. Crucially, the police managed to keep their telegraph working, despite rioters’ efforts to cut it, so that larger forces of police and militia could converge on the larger groups of rioters from different directions. However, for two to three days all Acton and Brown could do was react to the assaults of the rioters. The police did score one victory on the first day. At about 4pm a mob on Broadway was confronted by 200 police, a reserve kept at headquarters by Acton. A baton charge sent the rioters fleeing back uptown, leaving Broadway littered with stunned and disabled bodies.

The race riot also started on the first day. African-Americans were pulled off streetcars and beaten up. At this time only 12,500 African-Americans lived in the city and not in any distinct neighbourhood into which mobs would fear to penetrate. About four o’clock on 13 July a mob assembled alongside the Coloured Orphan Asylum on Fifth Avenue, only some streets from the smouldering Ninth District draft office. Shouting ‘Burn the niggers’ nest!’, the mob torched the building. The children had already escaped by the back way, the older ones leading or carrying the young to the safety of the 11th precinct police building. One account has an Irish boy, Paddy McCafferty, heroically leading the fleeing children.

Day two

Despite rain on the night of the 13th, the next morning dawned hot and bright. There is evidence that many sensed the change in the riot from draft protest to outright assault on representatives of the Republican government, and drew back. For instance, the Black Joke Engine Company took no further part in the riots and spent the following days keeping their own neighbourhood free of trouble. Many Germans who were prominent on the first day were also absent subsequently. The core of the German immigrant community, Kleindeutschland, between Division Street and 14th Street, was mostly quiet for the remainder of the riots.

Many Catholic Irish probably also drew back. Vigilance committees were formed in some areas to prevent rioting, and civilian volunteers stepped forward to help the police. Catholic priests and Peace Democrat politicians often arbitrated between the police and rioters. Sometimes the politicians bought time with promises of public money to buy men out of the draft. Trouble in the Five Points and Corlears Hook failed to materialise. Both accommodated most of New York’s brothels and the attendant criminal gangs. Five Points was the centre of the Sixth Ward (the ‘Bloody Ould Sixth’), notorious for serious riots in 1857 and centre of the garment district. It may be that local leadership, either through persuasion by politicians or coercion by criminals, staved off extension of the rioting.

The rioters were reduced to a hard core of several thousand, mostly composed of Irish immigrants. Attacks on African-Americans worsened; beatings now ended in murders. Black women were generally exempt unless they tried to defend their men, in which case they too were beaten. White women who consorted with African-Americans, including white prostitutes who took black clients, were also attacked and beaten.

An African-American man, Jeremiah Robinson, tried to escape dressed in his wife’s clothes, but was recognised and murdered by a mob. His wife was allowed to continue on to Brooklyn. The body of another black man, William Jones, was burned to ashes as if to expunge him totally from the neighbourhood.

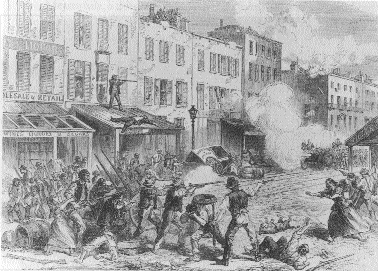

Rioters and militia fighting at a barricade on First Avenue, Illustrated London News, 15 August 1863. (New York Historical Society)

By the end of the second day most African-Americans had fled or were in hiding, otherwise the death toll might have been higher. Attacks on other targets also increased in audacity and brutality. The sight of a well-dressed person would bring shouts of ‘Down with the rich!’ and ‘There’s a $300 man!’. Such persons were usually chased and beaten, as were soldiers on leave and in uniform. Sometimes the victims were forced to give anti-Republican speeches, or stand rounds of drinks.

As an industrial city in wartime, New York had many armaments factories. On the first day a mob had successfully looted a gun factory on the corner of 21st Street and Second Avenue. Now attention turned to the Union Steam Works, only a block away, where there was a large supply of carbines and ammunition. The police managed to garrison the factory and a long battle against attacking rioters began. Eventually the mob gained possession, but only after the police had successfully removed all the guns.

In the morning, a large force of police and soldiers had a typical engagement with a mob that had been burning buildings on Second Avenue. Colonel Henry O’Brien and 150 men of the Eleventh New York Volunteers accompanied some 200 police. O’Brien ordered his men to shoot high and loaded his two cannon with blanks. The roar of the musketry and cannon did its work but two children on the rooftops were killed. O’Brien lived nearby and his house was looted, but his family was unharmed. Foolishly, or in a fit of bravado, O’Brien appeared at his house at two o’clock in the afternoon. He was set upon by a mob and tortured to death on the street by a group of men, women and boys.

The political response to the riots came on the second day. Governor Horatio Seymour visited the city and made a speech. He scandalised Republicans like George Templeton Strong by addressing a group which may have contained rioters as ‘my friends’. Seymour could not prevent Mayor George Opdyke, a Republican but not a radical, from telegraphing Secretary-of-War Stanton for soldiers to reinforce the police. Nugent was prevailed upon to proclaim the suspension of the draft, and the Common Council, popularly known as the ‘Forty Thieves’, established a fund to buy New Yorkers out of the draft.

Day three

This was the critical day of the riots, when reinforcements coming into the city would make their presence felt. The exhausted police, armed only with batons and pistols and with no training in riot control, gave way to soldiers armed with muskets and cannon. Regiments such as the Seventy-Fourth and Sixty-Fifth Regiments of the New York National Guard arrived by train or boat. Despite often sharing the rioters’ social class and ethnic identity, the soldiers extended little sympathy. Virtually all were War Democrats or Republicans and were indignant at this insurrection in their rear. For example, Sergeant Peter Welsh of the Irish Brigade wrote to his wife, who lived in New York, that the authorities should ‘use canister freely’ on ‘these bloody cutthroats’.

Attacks on African-Americans continued. Houses were broken into in search of blacks, and empty houses of African-Americans were burned. Shamefully, many landlords evicted black families to prevent their property from being damaged by mobs. Abraham Franklin, a crippled African-American coachman, was dragged from a house on 33rd Street and hanged from a lamppost. Worse, Patrick Butler, a sixteen-year-old Irish youth, cut the body down and dragged it through the streets by the genitals to the cheers of onlookers.

The day ended with another defeat for the authorities on East 19th Street. A mob gathered on the approach of an army patrol. Cannon were unlimbered and several rounds of grape shot were fired into the crowd. But the shooting from windows and rooftops continued and many soldiers were wounded. In other instances soldiers had entered houses to root out snipers. But in this case the commander had no stomach for that type of fighting and the soldiers retreated, ignominiously leaving their wounded behind them. Only the arrival of a second band of soldiers made possible their rescue.

The day ended with an increasing number of regiments arriving to take over from the exhausted police. Among them was the Seventh New York Regiment, composed of Republican bluebloods. Though Opdyke issued a proclamation that the riot was over, this was clearly wishful thinking. But the tide had definitely turned. The soldiers were well prepared to ‘use canister freely’, to hunt down snipers mercilessly and kill rioters at long or short range.

Day four

Life began to return to normal on Thursday. In the face of increasing numbers of well-armed police and army patrols, New York returned to work. The streetcars began to run again. Factories reopened, the railroads were repaired and telegraph communication resumed.

A native of County Down, Colonel Robert Nugent, 69th New York Volunteers (‘Fighting Irish’), supervised the New York draft. He was wounded at the battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862 and in May 1865 had the honour of leading the Irish Brigade at the grand review in Washington. (Michael J. MacAfee Collection)

As African-Americans reappeared on the streets, the police were able to save many from being chased and beaten, although one man was attacked and thrown into the East River to drown. But many African-Americans began to return to their homes.

Despite this, there was still sporadic violence and clashes with the army throughout the day. Fighting intensified on the Upper East Side, where rioters had built barricades in a desperate attempt to keep soldiers and police out of the area. The first party of soldiers to arrive were beaten off, but soon larger parties of soldiers arrived and a murderous firefight broke out. Soldiers broke into houses in pursuit of the defenders, and a series of house-to-house battles ensued. Rioters had been heard to remark: ‘Better to die at home than in Virginia’, and many of them did just that. Finally, the area was cleared and quiet. The city returned to some kind of normality.

Aftermath

The aftermath was muted. The number of dead was never fully determined. Officially, the death toll was 105, but rumours persisted about secret burials by families who feared the attentions of the authorities, or the dumping of bodies into the rivers. The count of the dead can be raised to 119, and without firm evidence it is not possible to go beyond that figure. The vast majority, about 80 per cent, were rioters. Twelve of the fatalities were African-American.

Despite the fury of New York Republicans, who wanted senior Peace Democrats arrested for conspiracy and treason, the Lincoln government left affairs in the hands of the local authorities. Since these were mainly Democrats, who were not eager to prosecute a large section of their voters, few rioters were ever indicted for serious crime. A couple of dozen received gaol terms for looting, but prosecutions soon fizzled out. This probably prevented a witch-hunt and the creation of anti-war martyrs. However, it also meant that the murderers of people like Abraham Franklin and Henry O’Brien went unpunished.

Politically, the advantage lay with the War Democrats and their leader, William Tweed. The Peace Democrats were now tainted with disloyalty and insurrection. It was the beginning of the reign of ‘Boss’ Tweed in city politics, supported by Tammany Hall and a solid Irish vote. Ironically, it was New York’s last great nineteenth-century riot, the Orange riot of 1871, that led to Tweed’s downfall, though the machine he created lived on.

The draft was resumed on 19 August, supported now by the presence of 20,000 soldiers. But overall the 1863 draft was a failure. Very few men were actually conscripted in the end. Although there were other drafts before the end of the war, it remained mainly a volunteer army. The government did find an untapped seam by taking African-American volunteers in large numbers—about 180,000 served before the end of the war. Also, it was found that recruiting expeditions of men from front-line regiments to their hometowns or cities were effective in combing out volunteers. In 1864 Robert Nugent led a successful recruiting drive in New York for the Irish Brigade. Nugent himself went on to be the last commander of the Irish Brigade in the Civil War. He had the honour of leading the Brigade at the grand review in Washington in May 1865.

Conclusion

The riots had mingled aspects of proletarian protest and race riot. In places there was even an air of carnival, as bar rooms and liquor stores were mobbed or looted. Mostly it was a resistance to the encroachments of police, officials and social reformers into formerly protected communal and familial spaces. The rioters attacked Republican homes and businesses and the perceived creatures of the Republicans: policemen, soldiers and African-Americans. There were also attacks on other symbols of modernity or reformism, such as Protestant churches, factories, and the new grain elevators on the docks.

The rioters themselves were not generally from New York’s ‘underclass’ or its criminal element. Most had never been in trouble with the law. They came from ‘respectable’ middle-class or working-class occupations—cart men, railwaymen, factory workers, bricklayers, carpenters, dockers and labourers. There is little doubt that most of the rioters were Irish. On the other hand, over 300 of the New York metropolitan police were also of Irish birth, some 20 per cent of the total. Probably an equal number were Irish-American. Only a handful failed to do their duty throughout the riot. Similarly, the militia and army regiments summoned to the city to support the police must also have had a large Irish component.

Regular troops enter the city to quell the riots-on the set of ‘Gangs of New York’.

Rival New York volunteer fire companies, often composed of members of violent street gangs, sometimes fought each other rather than the fire, as seen here in ‘Gangs of New York‘. They greatly resented not being exempted from the draft, as they were from militia service. Disgruntled members of the ‘Black Joke’ company instigated the initial attack on the Ninth Congressional District draft office. (Warner Brothers)

Riots had happened before in New York and in other American cities, and were to happen again. But these were dwarfed by the scale and duration of the 1863 disturbances. It was the context of the American Civil War that gave them their unique ferocity. The forcible drafting of men to fight in an unpopular war crossed an important line and set off the train of events that led to these disastrous July days. The draft riots can be considered as a civil war within the North, and indeed as a civil war among the Irish of New York in particular.

Toby Joyce is an engineer with a lifelong interest in the history of nineteenth-century Irish-America.

Further reading:

T. Anbinder, Five Points (New York, 2001).

I. Bernstein, The New York draft riots (Oxford, 1990).

A. Cook, The armies of the streets (Kentucky, 1974).

P. Quinn, Banished Children of Eve (New York, 1994).