‘Scientific warfare or the quickest way to liberate Ireland’: the Brooklyn Dynamite School

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, General, Irish Republican Brotherhood / Fenians, Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2008), Volume 16

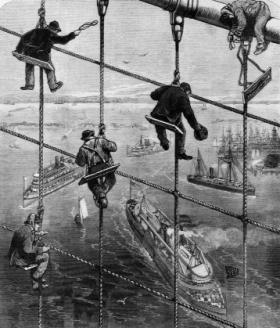

Workers lashing the stays of Brooklyn Bridge—not the city’s only claim to fame in the 1880s. (Frank Leslies’s Illustrated Newspaper, 28 April 1883)

In April 1883, local newspapers lamented the fact that Brooklyn, then a separate city from New York, was quickly developing a global reputation. Brooklyn’s new-found fame was not for its new bridge, then under construction: it had become renowned for harbouring dynamiters and militant Fenians who, according to the Brooklyn Eagle, were ‘bringing disgrace upon their asylum’ and causing an ‘intolerable affront’ to the city’s good name.

Bringing the war to Britain

Disillusioned with the failure of rebellion, the lack of foreign aid and the growing success of constitutional nationalism, many Fenians in the US began to consider alternative means to win Irish independence in the 1870s. Dynamite, Alfred Nobel’s 1866 invention, appeared to some to be the fitting remedy for the ailing ‘physical-force’ movement. Teams of dynamiters could strike on the doorstep of Westminster, and bring the war to Britain. Cheap and easily made, dynamite bombs, or ‘infernal machines’, held the potential to arm thousands of Fenians, thus removing past dependency on foreign powers for the provision of weapons.

Impatient with Clan na Gael’s hesitancy to employ Nobel’s new invention, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa and Patrick Crowe initiated a ‘dynamite campaign’ in 1880. Under the auspices of the revived Fenian Brotherhood and Rossa’s United Irishmen organisation, they bluntly declared their intentions to bomb political and economic targets in Britain. Crowe, a Galway emigrant who had settled in Peoria, Illinois, established the first ‘infernal machine’ factory in that city in 1881, claiming the same right for the manufacture of bombs as others held for firearms. An even more indiscreet talker than Rossa (no small feat), Crowe announced his plans to the world and even sent samples of his wares to local newspapers. After some months, it was decided to move the factory to a more populous Irish neighbourhood. By June 1882, consular dispatches to the London Home Office reported that New York Fenians were attending a ‘dynamite school of instruction’ in the Greenpoint area of Brooklyn.

Operated by a joint-stock company

The bizarre Dynamite Monthly, one element of what was commonly referred to as the ‘dynamite press’.

At the time, the Irish-born population of Brooklyn came to 78,814 out of a total of 566,689 (Brooklyn was the third-largest city in the US and growing fast). Neighbourhoods such as Greenpoint, Williamsburgh and Bushwick held particularly high concentrations of Irish, often over 30 per cent, and were fertile ground for ‘advanced nationalism’. The dynamite school’s main concern was, of course, the instruction of Fenians in the safe manufacture and transportation of explosives, namely nitro-glycerine. Yet the school also purported to be a legitimate business that was operated by a joint-stock company. Profits were to come from sale of the articles manufactured in the school during the training process. This proved to be wishful thinking, however, and the school was almost entirely financed by subscriptions to what was entitled the ‘Resources of Civilisation Fund’, collected by Rossa’s United Irishman paper. By the end of 1882 it amounted to the considerable sum of $3,401 and 67 cents.

In 1881 Rossa’s dynamiters had set off explosions in Liverpool, London and Salford with devices manufactured in the United States. As a result, smuggling infernal machines into Britain became difficult, as ports were heavily guarded and detectives carefully watched passengers with American-style portmanteaus. Hence the dynamite school’s primary goal was to teach volunteers how to make uncomplicated devices with easily found materials, as the bombs would now have to be manufactured on site, in Britain itself. These infernal machines were to be made from

‘a simple outside case of sheet iron, about ten inches square; the miner compartment contains the clockwork-movement that, at the time fixed, liberates a knife which cuts a string and lets fall a spring onto the percussion cap causing the machine to explode’.

The clockwork mechanism was a considerable innovation for the time and could be set hours in advance. This sophistication of design was the work of a chemicals expert who called himself Professor Mezzeroff. He was hired by Rossa to bring expertise and credibility to the United Irishmen, who were regularly ridiculed in the American and British press as incompetent bunglers who were no real threat to anyone except the gullible Irish immigrants from whom they conned money. In comparison to the professional Russian revolutionary, depicted as a master of chemistry and conspiracy, Rossa’s dynamiters fared badly. The Washington Post believed that while Rossa was full ‘of many words and few deeds’, Mezzeroff, by contrast, had devoted himself to revolution and was ‘to be more feared than a dozen Rossas’.

Without the specialist’s expertise, Rossa was no better than Don Quixote, tilting at windmills. Hence Mezzeroff took to the Fenian stage and began instructing ‘any man of average intelligence’ in the handling of nitro-glycerine and the mechanics of explosive devices. While his bomb-making school in Brooklyn progressed in relative secrecy, widespread public interest was ignited by Mezzeroff’s frequent lectures in 1883. Throughout the year he spoke at commemorative events and delivered presentations, to audiences averaging 150, of his bomb-making manual Dynamite and other resources of civilisation, which was sold through the United Irishman. With a thousand volunteers, Mezzeroff declared, he could win independence for Ireland. Once schooled by him, 500 would go to England and 500 to Ireland in order to instruct more volunteers in bomb-making. Soon, Mezzeroff predicted, all of Ireland would be armed. Interestingly, he believed that Ireland was particularly well suited to dynamite warfare, as the peat of the midland bogs was the perfect ingredient to soak up nitro-glycerine, thus allowing safe transportation.

![‘Agitators, attention! Irish societies and conventions will find the above little device [bombs and ‘infernal machines’ on the table] very convenient.’ (Puck)](/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/63_small_1247552120.jpg)

‘Agitators, attention! Irish societies and conventions will find the above little device [bombs and ‘infernal machines’ on the table] very convenient.’ (Puck)

In December 1883 the Brooklyn Fenians organised a series of lectures entitled ‘Scientific Warfare or the Quickest Way to Liberate Ireland’, which ran on consecutive Sunday evenings. Held at Columbia Hall on York Street, the lectures were chaired by Tipperary emigrant William Burke, head centre of the Tara circle of the Fenian Brotherhood. Speakers included dynamite enthusiasts like Mezzeroff, Rossa and his secretary Pat Joyce, along with ‘graduates’ of the dynamite school, all of whom argued that dynamite would imminently replace gun and cannon to become the sole method of warfare. Praise for Patrick Ford, the editor of The Irish World, was frequently aired, as another fund for ‘scientific warfare’ had just been launched in his paper and was viewed as a sign of an increasing consensus among all factions of ‘physical-force’ nationalism in the US. Another journal, the bizarre Dynamite Monthly, soon appeared and made up the third element of what was commonly referred to as the ‘dynamite press’.

When asked by a local reporter what they hoped to achieve with dynamite, one man in the audience contended that the aim was to ‘demoralise England by striking unawares at points where she least expects. We have tried agitation for 800 years and accomplished nothing’. Opinions on dynamite were far from unanimous, however, and on more than one occasion accusations came from the audience that the lectures were mere ‘vapouring’ and ‘blatherskite’ that amounted to nothing. As the months passed, the Columbia Hall lectures became little more than ferocious tirades on the merits of dynamite that drew few admirers. By the end of February 1884 as few as 30 people attended.

![‘Waging a windy war. The Irish kite [Irish independence] in the British kingdom.’ Attached is a pistol, a bomb, dynamite, ‘incendiary speech’, ‘down with England’, ‘murder the tyrants’, ‘arson’ and ‘assassination’. (Puck)](/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/63_small_1247552170.jpg)

‘Waging a windy war. The Irish kite [Irish independence] in the British kingdom.’ Attached is a pistol, a bomb, dynamite, ‘incendiary speech’, ‘down with England’, ‘murder the tyrants’, ‘arson’ and ‘assassination’. (Puck)

Did the dynamite school and lectures amount to anything more than ‘vapouring’? Ironically, one of the best-known Fenian dynamiters of the 1880s—Dr Thomas Gallagher—was a resident of Greenpoint but apparently had no connection with the dynamite school. Gallagher, a physician, conducted his own experiments and acted as the instructor for his ‘team’, one of whom was a 23-year-old Tom Clarke. In 1883 they travelled to Britain, under the auspices of Clan na Gael, to detonate explosives at various symbolic buildings, but they were arrested before any damage was caused. Only one of the Gallagher team—William Lynch—had attended the Brooklyn dynamite school and, five days after the group’s arrest, he accepted a government offer to testify against his co-conspirators. It appeared that the dynamite school did not prepare its pupils for arrest and the prospect of imprisonment. John Kearney, a self-professed student of Mezzeroff, was a key element of the Rossa-backed group that exploded three bombs in Glasgow in January 1883, at a gasworks, a railway station and a canal bridge. Ten men were arrested and imprisoned for their roles in the conspiracy, but Kearney himself walked, having turned queen’s evidence after his arrest.

The most competent graduate of the Brooklyn dynamite school, and one who could keep a secret, was Thomas Mooney. His fingerprints were on most of the Rossa-financed attacks of 1881 and 1883. An ex-RIC man from Clare, Mooney was unable to reconcile a career as policeman with his political beliefs and emigrated to the US in the late 1870s. Working under the alias James Moorhead, Mooney volunteered his services to Rossa and quickly became one of the dynamite school’s most accomplished students, eventually instructing others along with Mezzeroff. He first came to prominence when The Times named him for involvement in a failed attack on the London Mansion House in March 1881. Evading arrest, Mooney probably returned to America, but within a year he was in Britain once again to organise further attacks. His expertise helped prepare the home-made explosives that were used in the Glasgow attacks of 1883. In March of the same year, Mooney’s infernal machines caused considerable structural damage to the local government offices in London and, during the same night, he created huge controversy by placing a hatbox full of dynamite on the window-ledge of the offices of The Times. Mooney again escaped undetected and returned to New York, but what became of him after this is unclear.

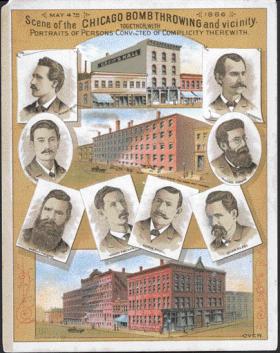

The eight anarchists tried for murder (on flimsy evidence, it was alleged) for the ‘Haymarket massacre’ in Chicago on 4 May 1886. The incident created a hostile climate for dynamiters across the United States, whatever their political colours.

Hostile climate in US after 1886 ‘Haymarket massacre’

By the late 1880s the dynamite school was already a thing of the past. Mezzeroff continued to lecture on dynamite in New York, but his small audiences were made up of curious passers-by rather than committed Irish republicans. By 1885 the US government began to harden its previously tolerant attitude towards radical Fenianism, while the 1886 explosions during a labour demonstration in Haymarket, Chicago, created a hostile climate for dynamiters across the United States, whatever their political colours. Above all, interest waned because the dynamite school had failed in its objectives. Infernal machines caused little damage, and the predicted economic hardships that they would bring to Britain failed to materialise. Moreover, the dynamite factions were riddled with informers and agents provocateur, who entrapped unsuspecting volunteers in fabricated plots in order to reap financial rewards from the Home Office.

The buildings where the dynamiters held their lessons and lectures are no longer standing in Brooklyn, and the Irish population there has greatly diminished. Few reminders exist of the fact that districts such as Greenpoint were once hotbeds of militant republicanism and the headquarters of conspiracies that stretched across the Atlantic.

Niall Whelehan is a Ph.D student in history at the European University Institute, Florence.

Further reading:

C. Campbell, Fenian fire (London, 2003).

W. O’Brien and D. Ryan (eds), Devoy’s post bag, 1871–1928 (2 vols) (Dublin, 1948, 1953).

M. Ó Catháin, ‘Dissident Irish republicans in late nineteenth-century Scotland’, in O. Walsh (ed.), Ireland abroad (Dublin, 2003).

K.R.M. Short, The dynamite war: Irish American bombers in Victorian Britain (Dublin, 1979).