Focus on the Fenians: the Irish People trials, November 1865–January 1866

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2005), Volume 13

An original watercolour of a Fenian flag based on the American ‘Stars and Bars’. It has four bars representing the provinces of Ireland and 32 stars representing the counties. (National Archives of Ireland)

On 27 November 1865 a special trial began at Green Street courthouse in Dublin. The Special Commission of Oyer and Terminer allowed the court to examine the cases of several prisoners associated with the Irish People newspaper and the Fenian Brotherhood. The most serious charge was treason-felony. The Treason-Felony Act had been passed in 1848 and allowed the government to try the Young Ireland leaders for treason without having to impose the death sentence, which was mandatory in cases where high treason was proven. The evidence required to prove treason-felony was also less exacting. The prisoners brought to trial before Justices William Nicolas Keogh and David FitzGerald had recently become notorious through media reports as members of the ‘Fenian conspiracy’. Among those charged were James Stephens, John O’Leary, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, Charles Kickham and Thomas Clarke Luby.

The origins of Fenianism

The Fenian Brotherhood was founded in Dublin on St Patrick’s Day 1858, when Joseph Denniffe met with James Stephens and Thomas Clarke Luby. Denniffe had just returned from New York with $140 received from John O’Mahony to fund the establishment of a secret revolutionary movement. The Fenian Brotherhood aimed to overthrow British rule in Ireland by armed insurrection. The pre-eminent Fenian John Devoy noted the movement’s direct connection to the Young Ireland movement of the 1840s. Stephens had been aide-de-camp to William Smith O’Brien at Ballingarry. John O’Mahony had led a large body of men in open rebellion in 1848, and Luby and O’Leary had been with James Fintan Lalor when he attempted a rising in 1849. After the failure of 1848 Stephens and O’Mahony fled to Paris, practising their organisational and conspiratorial skills in obscure poverty.

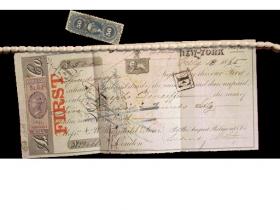

The £500 bank draft, found in an envelope at Kingstown Station on 22 July 1865 and payable to George Hopper, James Stephens’s brother-in-law, the link that convinced the lord lieutenant to suppress the Irish People. The bank draft was drawn on the August Belmont Bank in New York and was payable on three days’ notice at the Rothschild Bank in London. (National Archives of Ireland)

In 1854 O’Mahony moved to New York and was soon involved in Irish nationalist organisations like the Emmet Memorial Society. Stephens returned to Ireland the following year. He toured the country, making contacts with individuals and groups that were to form the core of the movement. The Fenians set out to absorb and unite other groups into a single multi-national secret society. O’Donovan Rossa was a member of the Phoenix National and Literary Society in Skibbereen, Co. Cork. These Phoenix Societies existed throughout Ireland and America and proved to be good initial recruiting grounds for the Fenians.

The leading figures of the Fenian or Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood were well-educated and literate men. They wrote memoirs, which are a good starting-point for research into the organisation. The most notable of these are John O’Leary’s two-volume Recollections of Fenians and Fenianism, O’Donovan Rossa’s Irish rebels in English prisons and John Devoy’s Recollections of an Irish rebel. However, archival sources in Dublin allow both the professional historian and the general public to access a wide variety of documents and photographs, letters and unpublished memoirs. The National Library of Ireland holds material from the Luby, Devoy, Stephens, O’Leary and O’Donovan Rossa papers. The Catholic University of America has made more of Rossa’s papers and O’Mahony’s papers available on-line.

The Irish People

In 1863 James Stephens decided that the movement had grown so large that it needed its own newspaper. He determined to set up the Irish People. Thomas Clarke Luby was to be the proprietor, John O’Leary the editor and O’Donovan Rossa the business manager. The paper was published from November 1863 until its suppression on 15 September 1865. Though Stephens wrote some of the early editorials, their writing was soon monopolised by John O’Leary and Charles Kickham. The National Library of Ireland has every issue available on microfilm.

One common refrain in the Irish People echoed the 1849 writings of Fintan Lalor, who proposed that the land of Ireland should be taken over by the people of Ireland. An editorial in February 1864 contained the following advice:

‘We have insisted, over and over again, that there is but one way in which Irishmen can benefit themselves fundamentally, and that is by regaining their lost independence, and at the same time re-conquering the land for the people’.

This call for the redistribution of land allowed the prosecuting barrister, Charles Barry, to accuse the Fenians of being socialists, an accusation repeated by newspapers in Dublin and London. In September 1865 Charles Kickham wrote an editorial, ‘Priests in politics’, which advised priests to stay out of politics and called for revolution:

‘Our beautiful and fruitful land will become a grazing farm for the foreigners’ cattle, and the remnant of our race wanderers and outcasts all over the world if English rule in Ireland be not struck down. Our only hope is revolution.’

However, before the issue was distributed, officers of Dublin Metropolitan Police’s (DMP) ‘G’ division raided the offices at 12 Parliament Street, a stone’s throw from their own headquarters in Dublin Castle. Further arrests were carried out throughout the city. As a result of the suppression of the Irish People, the police investigation of early Fenianism and the preparation of the prosecution cases, both historians and the general public have access to unique documents, photographs and other items, such as flag designs. This material can further illuminate the formative years of the most significant Irish nationalist secret society. An examination of a portion of this material reveals how Fenian finances reached Ireland from America by way of the Rothschild banking house in London.

The National Archives of Ireland (NAI) in Bishop Street, Dublin, is the main repository in Ireland for official documents relating to early Fenianism. The first place for a researcher to start is the records of the chief secretary’s office. The chief secretary was the official who was responsible for the day-to-day running of all aspects of government in Ireland. Every day the documents received at the office in Dublin Castle were given a number and a subject, and if they related to previous or subsequent correspondence the reference numbers to those files were also recorded. This correspondence was set down in separate books, alphabetically by subject and name, and in chronological order by date received. These indexes are huge leather-bound volumes, which must be handled with great care. Whereas straightforward searching under headings such as ‘Fenianism’ or ‘Stephens, James’ will yield results, many files of interest are listed under diverse headings. When using the chief secretary’s papers, random inquisitiveness can sometimes yield dividends for researchers.

Money-laundering

Another £500 August Belmont bank draft (13 July 1865), authorised by Joseph Denniffe, one of the original founders of the Fenian Brotherhood in 1858. (National Archives of Ireland)

An example of this is a subject reference in the 1866 index under the heading ‘Rothschild/John O’Leary’. The file that this subject relates to contains material on the financing of the Irish People and shows how openly the Fenians operated despite their secret status. It also shows the efforts that the DMP’s ‘G’ division went to in investigating their activities. The file referred to as ‘CSO RP 1866, 12,800’ contains the reports of Superintendent Daniel Ryan into an affair that began when an illiterate boy, Francis Larkin, found an envelope at Kingstown Station on 22 July 1865. According to Superintendent Ryan, the envelope contained an American bank draft and two letters. On 24 July Superintendent Ryan wrote a detailed report noting that, although both letters were in the same handwriting, one was signed ‘James Matthews’ and the other ‘John O’Mahony’. Ryan was aware that the addressee ‘James Power’ was a pseudonym used by James Stephens, head centre of the IRB in Ireland. In his report to the chief secretary Ryan stated that he believed that an ‘O’Donnell’ referred to in one of the letters was O’Donovan Rossa. Ryan’s reports in the file indicate the extent of police surveillance on the office and employees of the Irish People. For example, the DMP were aware that Rossa had used the name ‘Anthony O’Donnell’ when going to America on 24 June 1865 and that, though he arrived back in Dublin the day the envelope was found, he had not been to Kingstown.

The bank draft was for £500 and was payable to Mr George Hopper, a tailor of 80 Dame Street, Dublin. Ryan noted that Hopper was unaware that the police knew that he was James Stephens’s brother-in-law. The bank draft was drawn on the August Belmont Bank in New York and was payable on three days’ notice at the Rothschild Bank in London. On learning of this discovery, the chief secretary, Sir Thomas Aiskew Larcom, sent Ryan by the overnight mail-boat to London, where he met with detectives at Scotland Yard. In company with a Scotland Yard detective he interviewed Sir Thomas Rothschild at home on Saturday 28 July. It soon emerged that at least £5,807 15s 4d in August Belmont bank drafts payable by Rothschild’s had been cashed to the credit of John O’Leary between 31 August 1864 and 1 September 1865.

In his Recollections O’Leary, mistakenly, stated that up until the discovery of the lost envelope neither the police nor the government had much real information about the Fenians. Desmond Ryan in his biography of James Stephens felt that the contents of the letters convinced Lord Lieutenant Wodehouse to order the suppression of the Irish People. This one file of correspondence and police reports provides a unique insight into the unravelling of what came to be known in both official and media circles as ‘the Fenian conspiracy’.

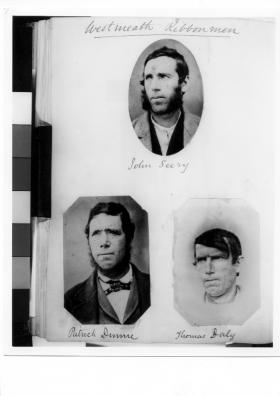

The Fenian look was urban and fashionable, especially when compared to these three suspected Westmeath Ribbonmen arrested in the same period under the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act.

Rothschild offered to come to Dublin to help the chief secretary. He allowed Ryan to copy a telegram and a letter that Hopper had sent to the bank asking for the lost drafts to be cancelled. Hopper was using his tailoring business to launder funds for the Fenians. However, given his relationship with Stephens and the fact that his business was advertised on the front page of every edition of the Irish People, it is difficult to understand how such activities could remain secret for long. This one investigation allowed the police to link the Irish People newspaper directly with the Fenian movement in America and with James Stephens, who was known to be the head of the conspiracy in Ireland.

Several collections of papers relating to Fenianism are held in the archive.

The Fenian ‘F’ papers were recalled to the chief secretary’s office on 22 January 1922 and brought to London, but unfortunately half of them were destroyed in the 1930s when the River Thames flooded.

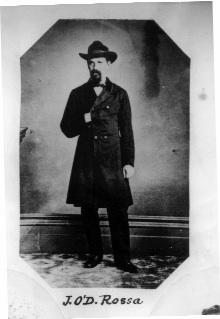

O’Donovan Rossa, like O’Mahony, strikes a Napoleonic pose.

Eventually what was left was repatriated on 22 April 1936, after lengthy negotiations. Twenty-two boxes were returned and were catalogued by the late deputy keeper of the then State Papers Office, Brendán Mac Giolla Choille, in the 1960s. He also wrote a guide to the Fenian papers for Irish Historical Studies in March 1969.

From 1865 there was a separate section in the indexes under the heading ‘Fenianism’. There are also constabulary reports and files from the DMP under the letter ‘P’ for police. Material might be filed under individuals’ names and under the names of the resident magistrates, who each have their own section in the indexes. In addition, the chief secretary’s office ‘Irish Crime Reports’ contain the names of several thousand leading Fenians and alleged Fenians, along with summaries of their arrests, alleged crimes and file reference numbers. The researcher might get lucky and find that the files are in the archives, but there are big gaps. There are about 100 boxes of files relating directly to Fenians here.

Photographs

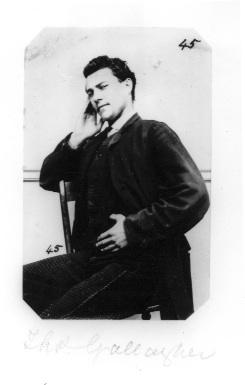

On the morning of 27 November 1865 the Special Commission sat in Green Street courthouse. It had been intended that 26 prisoners were to be tried over the next two months. However, two nights before the commission was due to begin James Stephens escaped from Richmond Bridewell with the aid of prison guards. He had evaded the initial round-up in September and was finally arrested on 11 November, along with Charles Kickham and others hiding with him in Sandymount. The commission moved to Cork in December and closed its proceedings on 2 February 1866. Yet two weeks later parliament passed a law suspending Habeas Corpus in Ireland. In the Irish Crime Reports there are books of returns of those arrested under the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act (HCSA), containing the names, descriptions and alleged offences of some 900 people. The then cutting-edge technology of photography was used to compile intelligence dossiers on Fenians. Hundreds of photographs of those arrested, taken while they were in custody, are stored individually in the NAI. They give a unique insight into the dress and, indeed, demeanour of the prisoners. Patrick Gallagher looks very relaxed and casual, even smiling at the camera.

Patrick Gallagher looks very relaxed and casual, even smiling at the camera.

Whereas the NAI’s collection of photographs are mainly of Fenians in police custody, the National Library of Ireland (NLI) holds a book compiled by Samuel Lee Anderson of very different Fenian photographs. (Samuel Lee Anderson was the son of Matthew Anderson, crown solicitor in 1865. Father and son prepared the cases against the prisoners tried at the Special Commission. In 1866 a younger son, Robert, was employed by Lord Mayo, the new chief secretary, to compile synopses of all files relating to Fenian activity. Robert’s expertise on the Fenians eventually led to his being brought to London to work with the Home Office and Scotland Yard as an adviser on Irish revolutionaries.) These photographs are generally cartes de viste or posed in photographers’ studios.

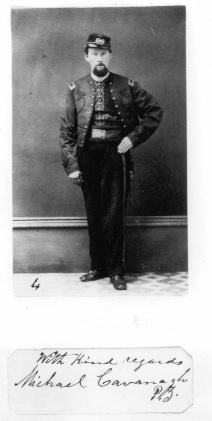

Michael Cavanagh in the uniform of the 69th New York regiment.

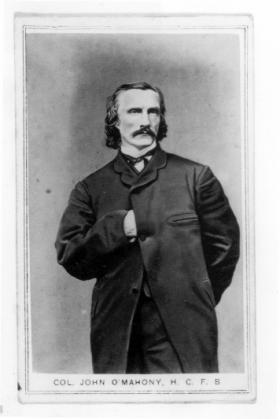

They show leading Fenians in poses that they personally wished to portray. John O’Mahony’s carte de viste bears his name and the initials ‘HCFB’, standing for Head Centre Fenian Brotherhood.

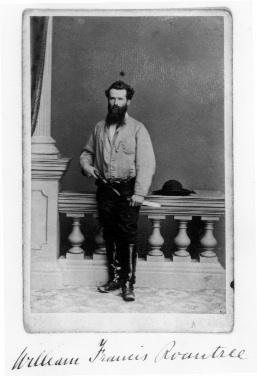

The Fenians in America were able to operate in the open. They held conferences, had printed letterheads, and openly declared their intention of invading Ireland with an army of militarily trained Irishmen who had participated in the American Civil War. This American influence has been described in The Fenians in context by Vincent Comerford, who noted that by the mid-1860s individual Fenians in Ireland were highly Americanised. The photograph of William Francis Roantree reflects this American style. Roantree had fought in Nicaragua with General Walker. His high boots, hat and pistols are more evocative of the American west than modes of dress in Victorian Ireland. Roantree’s role in the Fenians was as recruiter and organiser of the brotherhood’s members in the British army in Ireland. He took up this task in August 1864 when Patrick ‘Pagan’ O’Leary was arrested after attempting to swear in a solider on the bridge in Athlone. When Roantree was arrested, John Devoy took over his role in the organisation.

O’Donovan Rossa also sports a pistol in his portrait. Both he and O’Mahony strike Napoleonic poses, with one hand inside the jacket at chest level. Michael Cavanagh is photographed in the uniform of the 69th New York regiment founded by Colonel Michael Corcoran. The 69th was a volunteer regiment in the Union army and was thoroughly Fenian. It is striking that in most of the Samuel Lee Anderson collection and the HCSA photographs the subjects appear to be well dressed in fashionable clothes.

Vast quantity of documents seized

The NAI Irish Crime Reports also contain the evidence and legal briefs for the trials of alleged Fenians from 1865 to 1869 compiled by Samuel Lee Anderson. The box containing the briefs against Thomas Clarke Luby and others at the Special Commission contains five bundles of envelopes. There are nearly 500 numbered envelopes in total, which Samuel Lee Anderson and a small team picked from the vast quantity of documents seized at the offices of the Irish People and other addresses searched between the paper’s suppression on 15 September 1865 and the opening of the trials on 27 November. Envelope No. 1 contains a letter dated 8 September 1865 from James Stephens, using the alias ‘John Power’, which states that ‘This year—and let there be no mistake about it—must be the year of action’. The informer Pierce Nagle gave this letter to his handler at G Division, Superintendent Ryan. It had been intended for delivery to the Clonmel ‘B’s or Fenian captains. Other envelopes contain drawings of military fortifications and sheets of gridded paper for noting membership numbers. There are invitations to the 1861 funeral of Terence Bellew McManus, which the Fenians had stage-managed. Other items entered into evidence were the drafts of Irish People editorials in Charles Kickham’s tiny handwriting.

John O’Mahony’s carte de viste bears his name and the initials ‘HCFB’, standing for ‘Head Centre Fenian Brotherhood’.

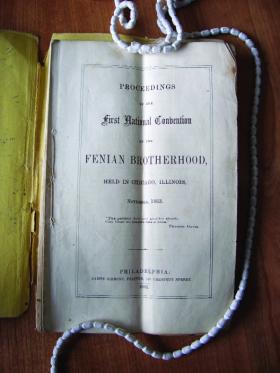

Methodical searching of each envelope can yield very important items. In No. 188, folded over to fit into the small envelope, is a printed pamphlet, Proceedings of the First National Convention of the Fenian Brotherhood held in Chicago Illinois November 1863. This pamphlet also contains what is possibly the earliest printed constitution of the IRB and is not in any Irish library. It shows how openly the Fenian Brotherhood operated in America. As well as lists of those in attendance, it contains the wording of O’Mahony’s opening address, the structure and regional officers of the Brotherhood in America, and an address to the people of Ireland, calling for armed insurrection and promising the support of trained Irish soldiers from America. This address was used at the Special Commission to prove the intended treason of those on trial. Pierce Nagle gave evidence of those he saw distributing or possessing copies of the pamphlet. The American wing believed that:

‘Nine tenths of the Irish people have at all times been ready, in heart and will, to dispute with armed hands the invader’s right to enslave or exterminate them’.

The Fenians in America were able to operate in the open, holding conferences, such as the one above, and even printing the proceedings. (National Archives of Ireland)

‘Hereditary Rebel and Milesian Pagan’

Another unique item folded to fit into its envelope is an original watercolour of a Fenian flag. In evidence at the magisterial examination of Patrick Heyburn, a barber, Michael Moore, a blacksmith (known in Fenian circles as ‘the pikemaker’), and Captain Michael O’Boyle of the Union army, on Thursday 5 October 1865, Moore’s landlord, George A. Gillis, admitted that he had painted the flag ‘out of my own head’ but had based it on similar ones he had seen. The design is unique and has never been published before. This flag prototype was based on the American ‘Stars and Bars’. It has four bars representing the four provinces of Ireland and 32 stars representing the counties.

Found in Moore’s possession were two letters from Patrick ‘Pagan’ O’Leary. O’Leary held eccentric views on religion. He was, according to John Devoy, the first Fenian ‘to wear the convict grey’. He hated the Catholic Church with the same intensity as ‘the cursed English’. In one letter he instructed Moore to address him in future letters as ‘O’Laegari, HR and MP’. He explained to Moore:

‘The cursed English way of spelling my name is O’Leary, and the old ancient Milesian pagan way is O’Laegari.

Yours O’Laegari

Hereditary Rebel and Milesian Pagan.’

One further useful item in the NAI collection is the bench notes of Judge Keogh for the Special Commission. He wrote his impressions of the evidence as it was presented during the trials and noted the envelope numbers relating to that evidence, thus matching up Samuel Lee Anderson’s case preparation to the actual course of the trial as seen from the bench.

With his high boots, hat and pistols, William Francis Roantree reflects a style more evocative of the American West than modes of dress in Victorian Ireland.

Though it is 140 years since the suppression of the Irish People and the first major Fenian trial, the material contained in just two Dublin repositories brings to life—through words, documents and images—the principle characters involved.

The IRB is believed to have disbanded in 1924.

Frank Rynne is a film-maker, record-producer, writer and postgraduate history student at Trinity College, Dublin.

Further reading

J. Devoy, Recollections of an Irish rebel (Shannon, 1969).

B. Mac Giolla Choille, ‘Fenian documents in the State Paper Office’, Irish Historical Studies XVI, No. 63 (March 1969).

J. O’Donovan Rossa, Irish rebels in English prisons (Dingle, 1991).

J. O’Leary, Recollections of Fenians and Fenianism (Shannon, 1969).

Catholic University of America on-line archive: http://libraries.cua.edu/achrcua/fenian.html