Charles Edward Burton: the first Irishman on Mars

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2006), Volume 14

A contemporary painting of Lord Rosse’s giant telescope at Birr Castle, Co. Offaly.

Nineteenth-century Ireland produced some of the most enthusiastic amateur sky-watchers in the British Isles, with the late Victorian era now being seen as the zenith of the ‘gentleman astronomer’. Astronomy had always been unique amongst the sciences, as anyone with an interest and some technical skill could greatly enhance knowledge of the subject. During this period wealthy Irish enthusiasts made important contributions that combined their academic skills with the hands-on engineering—often making their own telescopes and testing them to the limits. Just as the ‘spirit of the Empire’ mentality saw explorers mapping, categorising and explaining the far reaches of the globe, they did the same with the other planets of the solar system.

Lord Rosse

A large part of this group of Irish pioneers was centred on Lord Rosse, who had constructed the largest telescope in the world at his home at Birr Castle, Co. Offaly. Many Irish astronomical ‘names’ of the period were given their first chance by Rosse, as becoming an assistant at Birr Castle was often the first step for an interested young student to gain practical experience in observing the universe with scientific thoroughness. Not only did Birr offer knowledge on disciplines such as telescope-making and the proper procedures for the accurate recording of observations, life at the estate had the added bonus of numerous grand balls and dinner parties to attend on cloudy nights. Rosse certainly set the tone for the gentleman astronomer’s life of the day.

‘In spite of its glaring disparity between rich and poor, and the simmering political unrest, nineteenth-century Ireland produced more than its share of contributions to astronomy. Lord Rosse saw Birr less as a place where an able young man would spend a working life, than as a prestigious springboard for him to launch himself onto a distinguished career elsewhere’ (Chapman 1996).

It was through this agreeable route that Charles Edward Burton, the sickly son of the rector of Rathmichael church in Loughlinstown, Co. Dublin, started out on his short but eventful career in science. He had started as an assistant to Rosse in February 1866 at the age of 22. Although his ill health caused him to return to his family home in March 1867, he had by then learned enough to set up his own private observatory.

At that time the art of mirror-making for telescopes was in its infancy. A survey carried out by the London-based journal the Astronomical Register showed that, of the 48 private observatories run by its readers, the vast majority used the classic refractor (lens at both ends) telescope. Using pioneering skills learned from Lord Rosse (who had been able to cast and polish a mirror several feet in diameter using local labour at Birr just after the Famine), Burton set about equipping his own private observatory in Loughlinstown with two large reflector telescopes—one with an eight-inch mirror and the other with a twelve-inch. From then on he spent every clear night observing and making detailed notes on astronomical phenomena such as variables (stars that change in brightness), comets and the planets. His detailed reports to the amateur journals of the day soon saw his reputation grow, as they were meticulously written up and accompanied by detailed illustrations. He also regularly presented papers to the Royal Dublin Society, with his first report to the RDS being published in 1872 when he was only 26. He was elected as a member of the Royal Irish Academy in 1878.

Mars sensation!

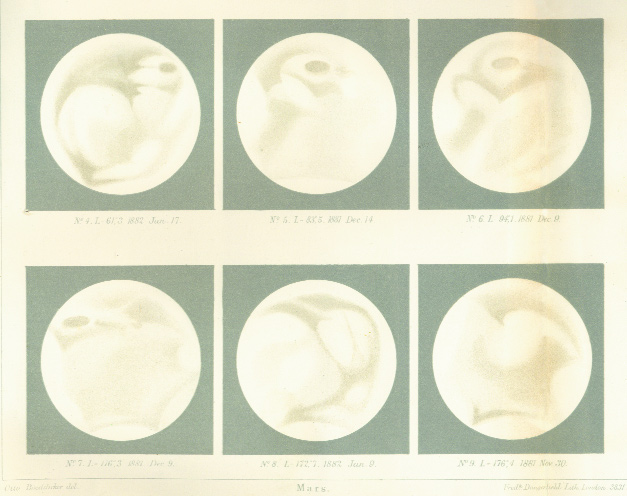

Ever since the invention of the telescope two centuries before, surface details on the other planets had always remained elusive to the human eye. Spotting markings on the tiny disc of Mars presented a challenge, with a fine line between seeing something and imagining that you had seen something. Burton himself had presented his first set of Mars observations to the Royal Dublin Society in 1873, complete with his own drawings. Although they show nothing remarkable, they reveal his growing drafting skills and the quality of his telescopes.

But the astronomical world would be stunned in 1880 when Italian scientist Giovanni Schiaparelli, working from the main observatory in Milan, sensationally claimed that he had spotted a network of ‘canals’ on the surface of the red planet.

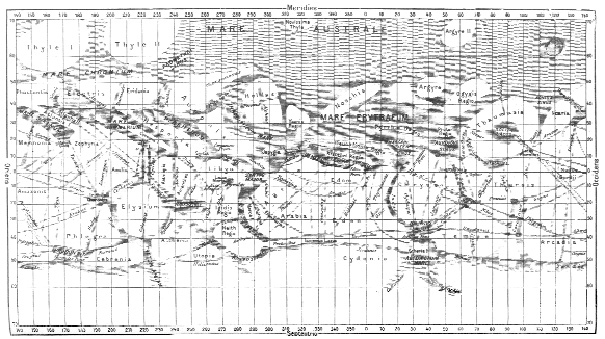

Italian astronomer Schiaparelli’s sensational diagram of the network of canali (natural grooves) that he reported seeing on the Martian surface.

Unfortunately the Italian meant canali or natural grooves, but this had been mistranslated into meaning artificial canals by the time his report reached English-speaking scientists. Although the Italian was genuine in his initial reports, his failure to correct the misunderstanding in time can now be seen as the origin of our modern myth of the ‘Martian’.

At the very moment when Schiaparelli had been making his first sensational observations of the red planet from northern Italy, Burton had been making his own drawings from Loughlinstown in south Dublin. He also saw similar features, and it was at this moment that the young Irishman with a reputation for good science entered the debate. Observing Mars had always been a matter of detective work, spotting the known features and then trying to decipher new details through periods of ‘clear seeing’—those moments when the Earth’s atmosphere above the astronomer settled down momentarily to allow the tiny disc of the planet to stop shimmering in the eyepiece of his telescope. He had to be patient, and he often commented that he was on the verge of a clear view but that ultimately ‘the air was not in prime condition’ for him to make the critical observation. Between 5 October 1879 and 5 January 1880 Burton had made nightly observations using his two telescopes, and at times had been able to use magnifications of up to x500.

‘Atmospheric conditions were usually good and I had some degree of confidence in the result’, he told the Royal Dublin Society when he presented his most important observations so far. Comments that he too had seen Schiaparelli’s new features set the astronomical world buzzing. He called them ‘remarkable objects’, and went on to report spotting ‘narrow dusty streaks’ that connected already known features on the planet’s surface, ‘. . . streaks that seem to traverse most of the Martian continents, often for distances equalling thousands of terrestrial miles, and that seem without any notable variation in breadth’.

Although many were convincing themselves that these new streaks could only be artificial constructions, Burton expressed his own caution:

‘Considering the difficulty of the objects… [interpretations] given these streaks by different observers hardly afford grounds for surprise. Great caution is necessary in asserting that any “canal” is a recent formation, considering our present almost total ignorance of the conditions.’

Intense scientific debate

During that period any astronomer who ‘discovered’ new features on another planet and then mapped them for the first time had the right to name them. But it was a tradition that often descended into pure cronyism—much like the naming of places in ‘darkest Africa’. Mars maps of the period soon became a patchwork of features named after everyone from the German kaiser to obscure figures known only to their astronomical friends. Now that Burton himself was in a position to name new features of his own, he asked his contemporaries that ‘perhaps I may be permitted to express an earnest hope that some system of nomenclature may be introduced which is free from… admitting the names of living persons’.

One of Burton’s early debates on what he had seen was with Nathaniel Green in the letters page of the Astronomical Register. Green was not only one of England’s most respected amateur astronomers but also a professional portrait artist who had once given painting lessons to Queen Victoria. Ironically, although Green had established his own private observatory on the island of Madeira to escape the bad weather of London, he had been unable to see Mars himself during the 1880 session because of bad cloud cover there. After studying Burton’s detailed notes and drawings, he questioned the true origin of the features, believing that they might only be an optical illusion caused by looking at the boundaries of the various tinted areas on the surface.

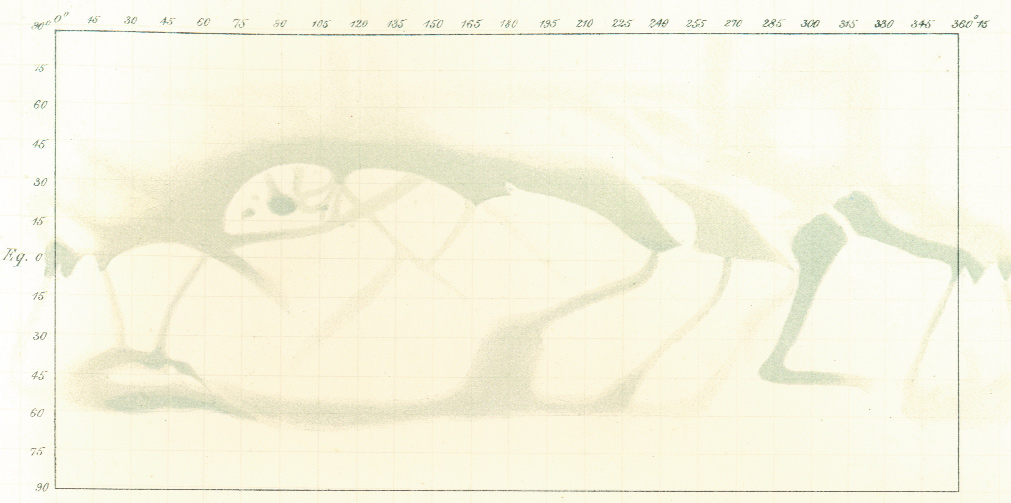

Burton’s first Mars map of 1879–80 (top) showed surface markings similar to the newly discovered ‘canals’. Despite bad weather, his expert skills are shown in further drawings of Mars during its close approach in the winter of 1881/2 (bottom). Within six months he would be dead. (RDS)

‘While all deference to Mr Green’s high authority in artistic matters, I cannot but think that he had been mistaken in supposing that the canals are merely boundaries’, was Burton’s respectful reply. Green’s answer showed his own willingness to give Burton the benefit of the doubt:

‘After Mr Burton’s exact descriptions of these forms, and the character of their appearance, it would be impossible to doubt their existence … there is a great tendance to question the existence of any form that had not been personally observed… we should be prepared to give a generous amount of credence even those drawings that seem to contradict each other.’

Speculation that an advanced race of Martians was building a network of canals similar to that on Earth became common currency, but very few astronomers held this view. For them only more detailed observation would solve the mystery. Although we now know that the canals were really a trick of the eye, caused when the astronomer’s brain subconsciously ‘joined the dots’ to make long lines where none really existed, the debate stimulated more interest in the planet than it had previously received.

Almost unnoticed amongst all this discussion was Burton’s other observation, which can now be seen as the first scientific evidence of clouds in the Martian atmosphere. Although actually being able to see these faint objects directly was impossible, Burton cleverly theorised that rising ‘ground mists’ in its atmosphere were responsible for the periodic obscuring of well-known features. His observation notes for 5 January 1880 state that ‘the southern region was much fainter and less definite than the northern and appeared yellowish … this observation seems to indicate that the southern snow had been covered, or possibly replaced by tinted clouds, as this region had been exposed continuously for several months of the sun’s rays’. Not until the twentieth century would the famous planetary scientist E.M. Antoniadi refer to these deductions of Burton’s as a work of ‘genius’.

Owing to the differing orbits of Earth and Mars, the two planets only come close every few years, so Burton was ready and waiting to make more detailed observations at the next opportunity in February 1882. Unfortunately, bad Irish weather combined with his continued ill health would hamper his plans, and he seems very embarrassed at the meagreness of the observations he presented to the RDS that year:

‘The weather having presented obstacles to a detailed and minute survey of the planet… the number of drawings had been smaller than on former occasion … I venture to lay them before the Society’.

After going on to describe observations of the planet’s polar snows and other markings, he made the academic equivalent of excusing himself until the next time:

‘These results are foreshadowings of what may be expected if … studying the planet under favourable conditions. How rare such conditions are in our climate, unfortunately … momentary glimpses of these minute details will require prolonged study in order to make further advance knowledge of the constitution of this planet—details so minute and complex that the smallest tremor of the image suffices to confuse and render them undecipherable.’

Sudden death

Earlier in his career Burton had taken part in a Greenwich Observatory organised expedition to observe the transit of the planet Venus across the face of the sun, and had even speculated that a lack of sharpness in the outline of that planet was proof of an atmosphere. The quality of those observations had got him noticed, and he was invited to join a new British expedition to Cape Colony to observe the next transit of the planet across the sun’s surface.

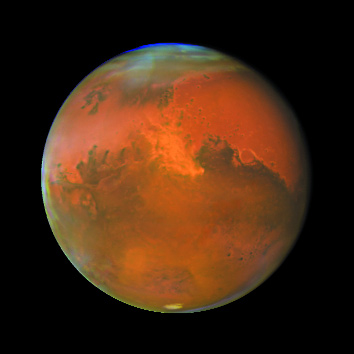

A recent view of Mars as seen from the Hubble space telescope. (NASA)

As his professional reputation was increasing, his private life was also developing. He had recently been engaged to a local girl named Grace after a long-drawn-out courtship. Being a shy person, Burton had started communicating with her by sending messages via their local milkman—a system that his sister (known as the wit of the family) had dubbed the ‘Milky Way’. The new young couple were enthusiastic church-goers and often worshipped at Castleknock church near Dunsink Observatory.

In hindsight Burton’s exhausting astronomical observations carried out during cold winter nights were probably not the best regime for a man of such a weak constitution. Although only in his mid-30s, the poor health that had caused him to leave assistant posts at both Birr and Dunsink finally and suddenly caught up with him. As he prepared himself for the summer Venus expedition, he suffered a heart attack and died whilst attending church on 7 July 1882.

His sudden death at the age of only 35 occurred just as his scientific career was taking off, and it was left to his good friend and fellow Irish astronomer Wentworth Erck, who had often invited Burton to his observatory in Bray, Co. Wicklow, to write his obituary for readers of the Astronomical Register:

‘His loss will be deeply felt by those who knew him well, for these laud him for his blameless life and courteous manners, as much as they respected him for his high scientific attainments and unsurpassed powers as an astronomical observer’.

Although his life was short, Burton wasn’t totally forgotten by the astronomical community, and in 1973 the committee of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) decided to name a small 137km-wide crater on Mars after him. This gesture was certainly a fitting tribute for the often forgotten Irish ‘gentleman astronomer’, but one wonders what a man who once publicly chastised his colleagues for naming Martian features after themselves would have really thought of it all.

Dominic Phelan is a writer specialising in the history of science and technology.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank the RDS Library for access to Burton’s papers.

Further reading:

P. Chambers, Life on Mars: the complete story (London, 1999).

A. Chapman, The Victorian amateur astronomer (Chichester, 1996).

P. Moore, On Mars (London, 1998).

W. Sheehan, The Planet Mars: a history of observation and discovery (Tucson, 1996).